Heightened public debt crisis risks in a more challenging environment

Highlights

- A sharp increase in public debt and large discrepancies across countries have been observed over the last decades, though many countries still have sound public finances.

- High public debt levels are of a particular concern for low-income countries.

- Higher risk of default in countries with weak public finances, especially in an environment of high-for-long interest rates.

- In case of default, coordination among creditors has become more complex as the profile of public debt has significantly changed.

After a decades-long steady increase, public debt ratios have surged with the Covid-19 pandemic. Even if they have decreased in many countries compared to their 2020 peak, high public debt levels are of a particular concern for low-income countries. According to the IMF, the majority were facing debt vulnerabilities as of August 2023, with 10 being in external debt distress and 26 at high risk of debt distress. Even if global public debt (in relative terms) remains lower than it was prior to the HIPC global debt relief process in the mid-90s, its current level and the rising trend are worrying, as similar levels could be reached again in the future. It might be even worse, in a complex environment of multiple types of creditors, high geopolitical tensions, elevated interest rates and rapidly worsening impacts of climate change.

The profile of public debt has significantly changed

Debt vulnerabilities can no longer be tackled in the same as way as in the past. This observation has to do with a drastic change in the composition of public debt that has occurred in the past decade. Firstly, domestic debt has become increasingly significant. Secondly, when it comes to the external share of public debt, the composition of external creditors has diversified sharply, with the rising weight of creditors outside the Paris Club (including China, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates) and of commercial private creditors (bondholders and banks). The latter share has increased substantially, notably (but not only) in lower and upper middle-income countries, exposing them to a change in global financial conditions and investor risk perceptions.

In addition, the type of instruments has also evolved, with a rising share of bonds, syndicated loans, debt backed by collateral (e.g. commodity-linked loans from the private sector or through bilateral official lending and cash collateral), and sometimes more opaque instruments (e.g. hidden debt in Mozambique and Zambia, the Chinese central bank’s swap lines). Moreover, after a continual decline since the early 2010s, concessional debt now accounts for a much lower share of the debt of lower middle-income countries, which implies that their public external debt has higher interest rates and lower maturities.

In this new context, and taking into account the growing importance of China as a bilateral creditor, coordination among creditors to address external public debt vulnerabilities has become more complex, notably in a climate of strained international relations. This complexity is highlighted by the recent developments in the international debt restructuring process and the implications of the growing importance of China as a key player.

The recent sovereign debt restructuring process is sluggish

In 2020, the Covid-19 crisis exacerbated existing debt vulnerabilities, particularly in low-income countries, and pushed public debt levels to record new heights. Indeed, the pandemic amplified public spending needs to mitigate the health and economic effects of the crisis, while revenues declined due to lower economic activity and trade flows, which in turn increased debt burdens. Many countries, especially those with an already high debt burden before the crisis, had limited financing access or faced very high financing costs. As a result, in 2020 several countries defaulted on their debt: Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Suriname, Zambia and Belize (and again in 2021), followed by Sri Lanka, Ghana, Malawi and Ukraine in 2022. During that same year, Belarus and Russia also defaulted, but this was due to Western sanctions and not their inability to pay back their external public debt.

To help deal with abruptly heightened financial pressures, the G20 put in place the Debt Service Suspension Initiatives (DSSI) for 73 eligible1 countries (broadly low-income countries). Among them, 48 benefited from the temporary suspension of debt service payments owed to their official bilateral creditors. However, the DSSI and the large emergency funds provided as a response to Covid-19 (by multilateral creditors and regional development banks) will not fix longer-term debt sustainability problems. Therefore, to prevent disorderly defaults, the G20 put in place the “Common Framework for debt treatments beyond DSSI” for DSSI-eligible countries. In 2020, Ethiopia, Chad and Zambia were the first to request debt restructuring under that framework. Ghana also joined last year, when the government announced it had ceased paying its public debt.

The first partial agreement was reached for Chad in early 2023, but this was mostly bilateral with commercial partners and did not include actual debt restructuring. Indeed, thanks to high oil prices, the country has no immediate financing gaps in its balance of payments. In the case of Zambia, an agreement was finally reached in June 2023, i.e. more than two years after it defaulted. Its official creditors (led by China) did not grant debt cancellation and instead opted for a restructuring consisting of grace periods and extended maturities. In October 2023, the agreement with official creditors was formalised and negotiations on a comparable restructuring deal with private creditors commenced. Consequently, Zambia is taking the final hurdles to move out of the debt crisis.

The least one can say is that, almost three years after the process started, the Common Framework has been disappointing. It has not yet succeeded in reducing the complexity and length of the restructuring process for eligible countries, and has failed in getting the private sector involved. The entire process is thwarted by the fact that non-Paris Club creditors in particular – such as China and private bondholders – are the most exposed creditors, while the entire process is based on Paris Club practices. This creates a lot of technical discussions, especially in an environment of high geopolitical mistrust between the West and China. Moreover, some countries that are eligible to participate in the Common Framework (e.g. Malawi and Djibouti, reported to have suspended its debt repayments to China and Laos) have not so far asked to restructure their debt under the Common Framework. Last but not least, there is so far no multilateral mechanism – outside the Paris Club – for tackling a potential public debt crisis in non-DSSI-eligible countries (e.g. Sri Lanka and Suriname). Hence, an alternative and more efficient debt restructuring framework appears to be required.

In this context, the IMF has recently set up the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR). This is not a decision-making process but rather an information-sharing mechanism which aims to help multilateral agencies and private and public creditors to identify key impediments to restructurings, together with design standards and processes that can address them. This framework is chaired by the IMF, the World Bank and India (as G20 chair), and includes a broad group of participants, Paris Club and non-Paris Club bilateral creditors (including China), debtor countries and representatives from the private sector. The group aims to clarify key concepts to support predictability and the fairness of debt restructuring processes.

Looking ahead, the success of the GSDR will largely depend on creditors’ involvement and willingness to compromise. Given their different profiles and the variety of debt instruments, and taking into account the rising tensions between the West and China (which notably insists on the participation of Multilateral Development Banks in debt restructuring and is reluctant to grant debt relief), it will be very challenging to put in place a new debt restructuring mechanism. Hence, future sovereign debt restructuring processes are likely to remain very complex and lengthy, dealt with bilaterally (mostly with China) or multilaterally according to a case-by-case approach, with negative consequences on debtor countries as well as on the recovery perspectives.

Public debt restructuring is no longer limited to external debt. As a matter of fact, a major dimension to address is also how to best handle the (rising) importance of domestic debt in total public debt. Indeed, its restructuring is becoming a more frequent tool for restoring debt sustainability, as highlighted by the ongoing experience of Ghana and Sri Lanka (but not Zambia) and, in the past, Jamaica. However, the restructuring must be done carefully. Indeed, the authorities have to look at who owns the domestic debt (e.g. the banking sector, pension funds) and the implications of a restructuring on the financial system, economy and households, to avoid deepening the existing structural problems (e.g. by hampering the banking sector).

China as the world’s largest bilateral creditor of low-income countries: implications

China has become, by far, the number one bilateral official creditor for low-income countries. Hence, any external debt restructuring negotiation usually involves China, and this has wide-ranging implications.

Historically, China has limited experience with debt restructuring processes, so the learning process will take time to facilitate debt restructuring talks, actual collective debt relief and to strive to find – if ever – a common level playing field. A constructive Chinese role is also made more difficult by the fragmented Chinese system, a lack of centralisation and coordination among the Chinese entities involved (notably China Development Bank, China Exim Bank and the People’s Bank of China) that have differing goals.

Another problem lies in China’s different perceptions about assumed financial responsibilities and creditor involvement. Beijing was seemingly frustrated by the DSSI because private and multilateral creditors were not involved. That partly explains – together with debt issues related to the Belt and Road Initiative projects – why Chinese banks have been less constructive in the Common Framework talks in the recent past, and why the Chinese authorities have repeatedly been calling for fair burden-sharing among all creditors, including multilaterals, in the case of debt restructuring negotiations. As a result, pressure of Beijing to end multilaterals’ preferred creditor status, potentially establishing a new collectively agreed common architecture with new rules – China intends to continue to favour its bilateral approach – is certainly going to increase in the coming months and years. This might affect the IMF’s role in stabilising the international financial and monetary system as an international lender of last resort for low- and middle-income countries.

This is corroborated by a recent study (Horn S., Park. B., Reinhart C. and Trebesch C., 2023) which showed that a rising number of countries (e.g. Argentina, Pakistan) in need of liquidity support amid financial and macroeconomic distress have used China’s central bank swap lines. Looking ahead, more countries could be incentivised to seek liquidity support and bailout from China instead of the IMF, with no conditionalities required but with higher interest rates. Such an evolution will be accentuated by geopolitical tensions and the building up of a new (and more chaotic) world order and system. This trend of shifting international crisis management, with a big role for China as international lender of last resort for many developing countries, is underway and – as highlighted by the 2023 study – could “have implications for the international financial and monetary architecture, becoming more multipolar, less institutionalised and less transparent”. Therefore, debt sustainability risks could increase and be more difficult to assess.

Which countries have a high risk of debt distress?

Looking ahead, the tighter global financial conditions (higher interest burden and lower access to capital markets) and low global growth prospects might further increase debt sustainability risks in the most vulnerable countries. Even without a debt crisis, net capital flows to emerging markets with weak fundamentals are expected to remain subdued, putting pressure on exchange rates, gross foreign exchange reserves and reducing emerging markets’ access to international capital markets. This might affect the rollover rate of existing debt as well as issuances of new debt. That being said, there are large discrepancies between countries and the market has so far distinguished between countries with and without sound fundamentals.

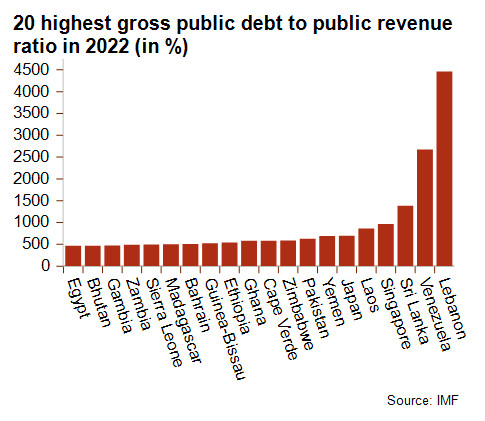

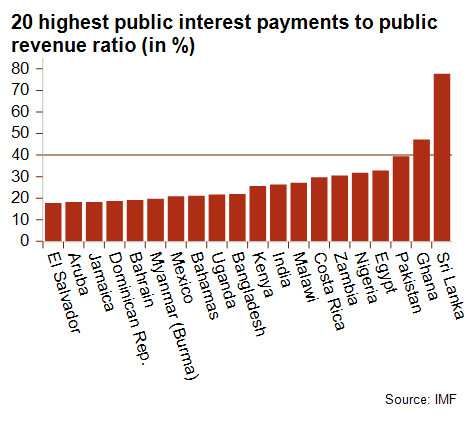

The most vulnerable countries are those presenting a high public debt-to-public revenue ratio and a high public interest payments-to-public revenue ratio. Among them, Ghana, Malawi, Sri Lanka, Zambia and Suriname are in default. Currently, Ethiopia and Ghana are discussing a debt restructuring under the Common Framework whereas Sri Lanka is negotiating a similar outcome with its private and official creditors. In addition, the risk of default in Laos and Pakistan is very high, as highlighted by their MLT political risk, currently classified in Credendo’s highest category of 7/7.

Alongside developing countries, developed economies can have very high public debt-to-revenue ratios, such as Japan and Singapore. However, the risk is more limited for such countries as they usually have public debt with a long maturity and lower interest rate (therefore they are not included in the graph below as the interest payments-to-revenue ratio is low).

Recent sovereign defaults (e.g. Sri Lanka in 2022, Lebanon 2021–22) have highlighted the close relationship between sovereign default and risk of a balance of payments crisis. After all, a sovereign default driven by poor public finances (e.g. Sri Lanka) could rapidly lead to a balance of payments crisis – sharp depreciation in the exchange rate and depletion of the gross foreign exchange reserves – amid notably large capital outflows. What’s more, even without a default, very weak public finances can have spillover effects on the economy by triggering capital outflows (e.g. Egypt), making new financing more difficult and expensive to attract, even for the private sector. Moreover, it is very likely that the authorities will have to consolidate their public finances by reducing their spending (e.g. lower subsidies) and/or increasing revenues (e.g. higher taxes) and implementing structural reforms. This can have a lingering impact on economic performance, further complicating the economic rebalancing process and return to a more sustainable level of public debt. Last but not least, a high public debt burden implies that the authorities have less fiscal space to implement expansionary fiscal policies, particularly in case of external shocks. This reduces growth prospects and makes the country more vulnerable to external shocks.

Another aspect to take into consideration is the growing impact of climate change, which could lead to a rising call for debt service suspension for countries hit by extreme natural disasters. This option has already been used via “hurricane clauses” in bonds issued by Barbados and Grenada. Recently the UN proposed a debt service suspension for Pakistan after the devastating floods in 2022. Even if the proposal was not implemented, it shows that in a world of increasingly acute climate change impacts, more countries will face debt service difficulties following extreme natural disasters. The risk is seeing sovereign debt vulnerabilities persist, as the rising frequency and intensity of extreme climate shocks could prevent a full economic, financial and physical recovery from taking place as the country is hit by a new severe natural disaster, leaving it in persistently poor economic conditions and unsustainable levels of public indebtedness. Moreover, the colossal investment needed to mitigate and adapt to systemic climate change will weigh heavily on debt positions in developing and emerging countries. Therefore, the call for debt service suspension and also climate change-related debt relief will become increasingly resounding over the years, especially in Africa. Such issues are currently hotly debated, making reform of the international debt and financial architecture inevitable in the future.

Analysts: Raphael Cecchi (R.Cecchi@credendo.com) and Pascaline della Faille (P.dellaFaille@credendo.com

1 Countries eligible to request Debt Service Suspension under the G20 DSSI were countries on the UN list of Least Developed Countries and countries eligible to borrow from the IDA at the time the initiative was endorsed in April 2020. To qualify for the DSSI, countries could not be in arrears with the IMF and/or the World Bank (ineligible IDA borrowers were Eritrea, Sudan, Syria and Zimbabwe).