Brazil: Upgrade of the MLT political risk rating from category 5/7 to 4/7

Highlights

- Higher commodity prices are supporting the economy and narrowing the current account deficit to historically low levels.

- External debt-to-current account revenues stand at a decade low, lowering financial risks.

- Despite monetary tightening by the USA, Brazil has not seen any large capital outflows and is even viewed as a safe haven amongst emerging markets.

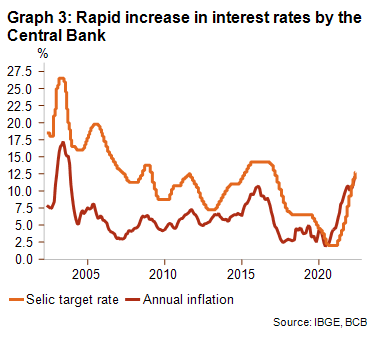

- Brazil is battling the highest inflation since 2003 with aggressive interest hikes.

- The Achilles heel remains the public finances, despite recent major structural reforms.

Pros

Cons

Head of State and Government

Population

GDP per capita

Income group

Main export products

Upgrade of MLT political risk from category 5 to category 4

Brazil’s MLT political risk rating was downgraded in July 2016 to category 5/7 in view of the deterioration of the economic fundamentals and increase in financial risk. A commodity boom unwound, resulting into two years of recession in 2015-2016 and a drop in current account revenues, while a confidence and political crisis also erupted due to corruption scandals. However, in the past five years macro-economic fundamentals have been vastly improving as the confidence and political crisis has abated, some necessary fiscal reforms have been implemented and higher commodity prices have supported the economy. As a consequence, economic fundamentals and financial risks have significantly improved, and Credendo has decided to upgrade the biggest Latin American economy to category 4/7.

Higher commodity prices are good news for the current account balance

Higher commodity prices (especially for fuel, metals and food) are clearly benefiting the large commodity exporter. First of all, Brazil is the world’s fourth-biggest food exporter – after the USA, the Netherlands and Germany – with soybeans being the most important subcategory. Furthermore, it is the second-largest Latin American ore and metals exporter (after Mexico), with iron ore being the most important subcategory. Moreover, the country is the fifth-largest lithium and fifth-biggest copper producer in the world, which could also benefit the country in the long term given the clean energy transition. Lastly, since 2017, the country has been a net fuel exporter (and the second-biggest oil exporter in Latin America, after Mexico). As a result, the current account deficit has historically been relatively small since 2020 (see the current account-to-GDP ratio in graph 1). The current account deficit forecast for 2022 is -1.5% of GDP, in line with the past three years, which is clearly smaller than the historical average of -3% of GDP between 2010 and 2020. In the medium term, the current account deficit is expected to deteriorate slightly but remain modest at almost -2% of GDP. Looking to the future, diversification will be one of the main challenges as Brazil’s dependency on commodities (though it represents a broad category) makes it vulnerable to a commodity downturn, as happened in the second half of 2014 and in 2008. Another important challenge is the rapidly rising level of deforestation in the Amazon in order to cultivate more land for agriculture, as this could sharply increase the risk of severe droughts and sustainability is a concern in rich and middle-income countries. The USA and the EU have already introduced legislation in order to reduce the import of food produced on illegally deforested lands, such as the Amazon.

Brazil is perceived as a ‘safe-haven’ in the emerging market but public finances are a concern

In recent years, Brazil has seen its current account deficit financed by foreign direct investments (FDI). This is expected to continue in the coming years. The portfolio balance turned positive in 2021, whereas it was negative between 2016 and 2020 following the sovereign’s downgrade below investment grade. Looking ahead, the monetary policy tightening by the US Fed is a risk as it could lead to capital outflows in emerging markets. However, as a large commodity exporter with reasonably solid macro-economic fundamentals (though the public finances are a concern) and limited trade and financial links to Russia, investors are currently seeing Brazil as a sort of ‘safe-haven’ in the emerging market, mitigating the risks. Nevertheless, tackling the high public debt (93% of GDP in 2021) will remain a big concern and could lead to investor risk aversion and capital outflows in the medium term.

External debt-to-current account revenues stand at a decade low

Financial risks have significantly decreased in recent years. External indebtedness is moderate at less than 40% of GDP and almost 180% of current account revenues at the end of 2021. Moreover, the external debt-to-current account revenue ratio stands at a decade low. Additionally, the financial risks are mitigated as around 90% of debt is medium to long-term debt. On top of that, the persisting huge liquidity buffer that was built up in the 2000s also lessens the financial risks. As of the end of February 2022, reserves covered the equivalent of about one year of imports. At the end of 2021, foreign exchange reserves covered almost 56% of the total external debt and more than 3.5 times the annual debt service. Debt service has been clearly improving as well in the past year. That being said, a major concern is a significant deterioration of the fiscal position, which could impact external debt dynamics.

The biggest Latin American economy is facing tepid economic growth

Brazil recovered from a relatively modest contraction of real GDP, compared to other Latin American countries, of -3.9% in 2020 with a strong economic rebound of 4.7% in 2021 (see real GDP growth in graph 2). However, economic growth is losing steam despite the benefits of higher commodity prices. Real GDP growth is expected to be a meagre 0.8% in 2022 because of the impact of monetary policy tightening in the past year combined with political and policy uncertainty in the run-up to the presidential elections in October. In 2023, political uncertainty is expected to wane but harvests are at risk of lower yields due to the dependence on Russian fertilisers. Therefore, real GDP growth is expected to increase but stay relatively low at 1.4% in 2023. Thereafter, economic growth is likely to remain rather tepid: the IMF forecasts real economic growth of about 2% (slightly higher than the historical average real GDP growth of 1.3% in 2009-2019). This can be explained by structural challenges such as subpar infrastructure, bureaucratic red tape, tax system complexity, inadequate access to credit for companies and high trade barriers. Downside risks to the forecast include the vulnerability to droughts, severe unrest, a new deadly wave of Covid-19 (though 77% of Brazilians have been fully vaccinated) and a significant deterioration of public finances. On the upside, if the higher commodity prices prove to be long lasting or productivity-enhancing reforms are introduced by the government, higher economic growth is possible.

Brazil is battling the highest inflation since 2003

The Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) is fighting double-digit inflation. Inflation stood at 11% at the end of March 2022, the highest level since 2003 (see the red line in graph 3). Inflation has risen due to increasing global food and energy prices, supply bottlenecks and the severe drought conditions in the past year, which have led to higher electricity prices because of the costly replacement of hydropower with fossil fuel. As a result, the BCB aggressively raised its Selic policy rate to 12.25% at its last meeting in May 2022 from 2% in March 2021, a historically low policy rate (see the orange line in graph 3; the red line represents the annual inflation rate). Further monetary policy tightening can be expected this year, although probably at a less aggressive pace, as inflation is expected to decrease in the coming months (to 6.7% at the end of the year) as the impact of past monetary policy tightening manifests and given the severe drought is over. The appreciation of the Brazilian real vis-à-vis the USD since the start of the year could also counter the price increases of imported fuel and energy.

The Achilles heel remains the public finances, despite recent important structural reforms

Reforms have been implemented in previous years to keep public finances on a sustainable path. Since 2016, the federal government has been limited by the constitutionally mandated spending cap, which freezes spending in real terms. Also, a relatively mild but important pension reform was approved in 2019. Moreover, some privatisation plans are still in the pipeline to be implemented before the elections (the biggest being the privatisation of Brazil’s power company Eletrobras), though it remains to be seen if this can be done in time. Nevertheless, public debt has been increasing in recent years but at a significantly slower pace than anticipated before the reforms. Public debt jumped to a high 99% of GDP during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 (see public debt in orange in graph 4; the red line represents the overall fiscal balance), which is substantially higher than the average for emerging markets. Thanks to the economic recovery, public debt declined to 93% of GDP at the end of 2021. Looking ahead, the commodity-price boom will buoy oil royalties and tax revenue from mining and agricultural companies in 2022, decreasing public debt to 92% of GDP, which is nevertheless still a high level. Despite the high public debt, public interest payments are at manageable levels for the country. Furthermore, the overwhelmingly domestic investor base (about 88% of debt is in domestic hands), high composition in Brazilian real (representing about 94% of debt), large liquid assets and substantial Central Bank holdings of Treasury debt mitigate the risks. Looking ahead, the next president will need to introduce further fiscal reforms to keep public finances on a sustainable path.

Analyst: Jolyn Debuysscher (J.Debuysscher@credendo.com)