Global supply chains: Multiple factors mean disruptions could last until 2023

Highlights

- The disruption of global supply chains is expected to gradually ease but could last until 2023.

- Multiple factors are at play, from Covid-19 lockdowns to climate conditions.

- There is a large mismatch between supply and demand.

- In the meantime, commodity prices and shipping costs are soaring.

- Whereas some sectors are suffering from the situation (e.g. automotive, construction) others are thriving (e.g. semiconductors).

Global supply chain under pressure

When the Covid-19 pandemic crippled international trade, freezing supply chains, it was thought that global supply chain disruptions would be temporary. However, they are continuing to wreak havoc in many sectors. The difficulties arise from a combination of factors, some temporary, others structural.

Consumer demand is there…

With the reopening of the economies, the global demand recovered rapidly. This is partly explained by the savings accumulated during the pandemic, the very accommodative fiscal and monetary policies, and the huge recovery plans that emerged across the globe, with the objective of focusing in particular on green transition. The latter consumes a lot of metals, wood and energy (more gas and less coal). On the consumer side, many figures highlight the recent increase in consumer demand, such as the high number of vehicles sold in the United States (steel and aluminium-intensive) in April 2021 (a level not seen since 2005, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis) and sales of new homes in the USA reaching a 14-year record and consuming a lot of wood and cement among other things. While demand is strong, supply is struggling to keep pace.

…but supply is struggling to follow

The sharp demand along with limited supply has many consequences, among other things for commodity prices. As shown in graph 1, many commodity prices have surged since the beginning of the year amid supply/demand mismatches as well as weather conditions, Covid-19 disruptions, OPEC+ decisions, natural disasters and worker strikes at sensitive production sites. The surge in commodity prices is affecting the margin of manufacturers reliant on raw materials as inputs. The mismatch between supply and demand is affecting not only commodities but also the price and availability of intermediate goods (e.g. semiconductors) and labour.

Faced with this challenging situation, companies often have little choice but to pass on this increase, or part of it, to the consumer, fuelling inflation. In some cases, they have no choice but to reduce production (amid among other things a shortage of materials and labour) or in exceptional cases stop production temporarily (e.g. the UK’s major industrial fertiliser plants and the automotive sector). The shortage of materials and/or equipment is the biggest limit to production, according to a survey of European manufacturers. Graph 2 below shows that this is a very exceptional situation. Globally, the sectors most affected by the shortages are the automotive, electrical equipment, materials, transport and construction sectors.

Longer distances amid disruption in production caused by Covid containment measures

According to an OECD analysis, the distance travelled by imported products increased in 2020. This is partly explained by the multiple lockdowns across the world, which affected production. Therefore, most importing companies turned to China (and the South East Asia region) to fill the supply gap left by Western/closer companies.

This increase in distances travelled for goods, as well as competition between importers to secure transport from China, have therefore contributed to the increase in the cost of shipping (see graph 3). In addition to having to change suppliers, companies are facing difficulties in having orders shipped, which is leading to a further increase in cost. Indeed, global shipping continues to be afflicted by a shortage of ships, delays and congestion at ports as a consequence of the surge in demand for merchandise transport, which in turn means a lack of containers, as well as Covid-19-related issues forcing the sporadic closure of port activities. This situation worsened with the blockade of the Suez Canal in March 2021 and the closure of international ports, as we saw with the closure of a terminal at the Chinese port of Ningbo in August 2021.

Geopolitical tensions are an additional hurdle

Supply chains are also very much impacted by the geopolitical context. Technology in particular, in addition to shortages due to the very strong demand and supply issues, has become a geopolitical issue, with semiconductors being part of the battle between the USA and China, with Taiwan in the middle. Sanctions have been imposed by the USA on the sector, sometimes to the detriment of their own industry, to curtail Chinese tech development and this has led companies to review their logistics strategies.

In addition, supply chains are sometimes not very transparent, even for different stakeholders in the same supply chain. This makes it impossible to identify the different bottlenecks and therefore to solve the problem. Moreover, the supply chains are, depending on the sector, very geographically dispersed with a large number of suppliers. This is the case, for example, with automobiles, for which more than thirty thousand spare parts are required, which further complicates the supply chains.

Low inventories

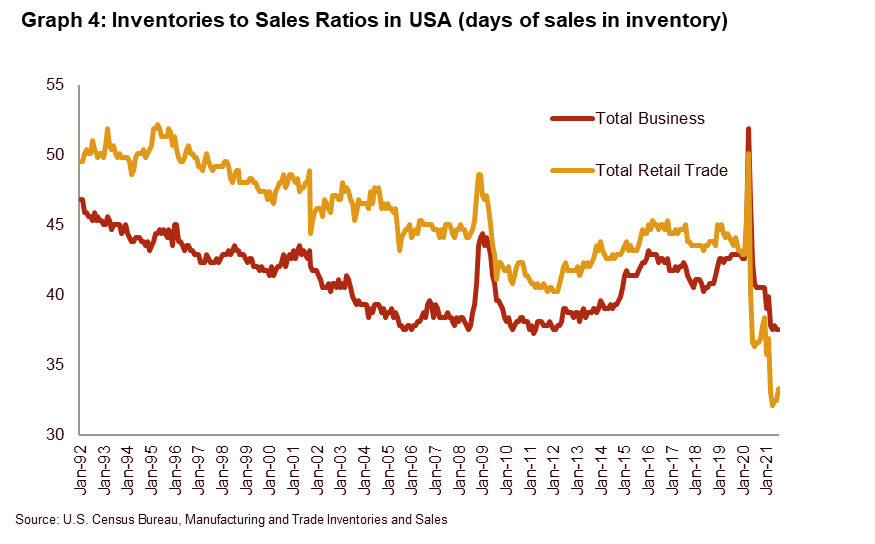

As supply chains are disrupted, prices rise, basic or sophisticated materials are less available and importers compete to fill the smallest container on a cargo ship. As a result, companies’ inventories are at a low level. Graph 4 shows that US companies have 38 days of inventory (43 days for the ‘normal’ year 2019) and that this number is pushed even lower for retailers (33 days in July 2021 vs. 44 days for the ‘normal’ year 2019), while at the onset of the pandemic, inventories were very high – given the unexpected Covid-19 outbreak.

What are the consequences of this disruption of the supply chains?

In the short term, supply chain disruptions are likely to continue in 2022 but should gradually ease. However, any new setback could prolong it until 2023. All in all, while supply chain disruptions could cap the ongoing economic recovery, they are unlikely to stop it, as other factors such as large infrastructure plans in the USA, the Next Generation EU fund and strong demand are most likely to offset the impacts of supply chain bottlenecks.

Also, the Covid-19 pandemic and its consequences for the supply chain are leading companies to reposition themselves. The current just-in-time supply chain model with a variety of suppliers in a variety of countries has revealed some limitations. Nowadays, the question of the reshoring of industrial production seems to be gaining momentum (see graph 5). Although this theme of reshoring is not new – indeed it was already discussed and in some cases implemented by companies like Ford, Whirlpool, Harley-Davidson and Universal Electronics, following the trade war launched by Donald Trump – Covid-19 acted as the catalyst. However, the transition from global supply chain to regional supply chain is expected to take time, with many divergences across the regions.

The trade barriers (e.g. subsidies, tariffs, quotas, regulations, sanctions) put in place before the pandemic on the back of geopolitical tensions are not going to disappear anytime soon. On the contrary, such practices should intensify in the coming years. The transfer of tech design and equipment between economies and multinational firms in particular should become increasingly subject to government intervention. This should additionally lead to the development of regional production capacities, especially in the areas of technology (as shown by semiconductors) and essential drugs (as demonstrated by the current health crisis).

The transition to regional supply chains and development of regional production capacities should materialise with new investments in technology (internet of things, 5G, artificial intelligence, etc.) and automation. Entire sectors could restructure (e.g. retail, automotive, aerospace), leading to a mismatch in the labour market. In the medium to long term a reallocation of capital and labour on a large scale can therefore be expected. The adjustment could take time and the current economic transition could take much longer (as illustrated by Brexit).

Analyst: Matthieu Depreter – m.depreter@credendo.com