Argentina: Locked in a vicious circle with no end in sight

- President Fernández’s first year in office has been very complex, with a deep recession and higher poverty levels amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Government restructuring of commercial debt has bought time but the public debt stock remains unsustainable in the long term.

- A devaluation to stem the decline of the peso and foreign exchange reserves looks increasingly likely.

- Uncertain IMF talks could result in a weak deal which maintains structural weaknesses and erodes investor confidence.

The Covid-19 shock is making government policy-making extremely complicated

Argentina’s political situation remains marred by uncertainty. When Alberto Fernández became President in December 2019, he brought Peronist parties back into power amid an economic recession. Then, the sudden Covid-19 shock broke out and has rapidly become the new government’s top priority. Since March, one of the world’s longest and strictest lockdowns has been in place. Containment measures have been gradually eased, although the number of new daily cases was still on the rise at the end of September. This year, the economy collapsed further, and Argentina defaulted for the 9th time on its sovereign commercial debt before broad government debt restructuring was agreed by private bondholders and extra capital controls were introduced. Renegotiating the USD 44.9bn IMF debt is the next challenging step on the government’s agenda for the coming months. The Covid-19 crisis has made policy-making even more complex than it was just a year ago, especially considering President Fernández’s rapidly falling popularity on the back of extended lockdown measures. Looking to the mid-term elections in October 2021, he could lose influence within the ruling coalition to the advantage of Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who is rather opposed to an IMF deal, and see the Peronist coalition lose support among the population. The recession context could favour a return to unorthodox and populist policies including enhanced state interventionism and extended exchange controls. This could put talks with the IMF in jeopardy as conditions such as reducing the fiscal deficit via spending cuts and pension reforms are impossible to accept for a government facing the threat of social unrest. Looking ahead, the health and economic crisis, rising social protests, strikes and business disruptions amid high unemployment and poverty, and potentially populist macroeconomic policies threaten to severely affect the fragile economic recovery in 2021 and beyond.

Argentina is locked in a vicious circle with no end in sight

The Covid-19 shock has badly affected Argentina’s weak economy, which has no buffers, and exacerbated the country’s very precarious economic and financial situation. Prior to Fernández’s election, the country had just been facing another deep currency crisis and mass capital outflows in August 2019 along with hyperinflation. This triggered the re-introduction of currency controls, led the Central Bank to raise interest rates to sky-high levels and kept the Argentinian economy in recession and investor confidence at a nadir. In this context, newly elected President Fernández suspended the IMF programme after most disbursements (77% of the bailout) had been made. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to strict containment measures and caused global demand to plunge, thereby leading to a collapse of domestic activity since March. The recession in place since 2018 will deepen further this year to around 12% before a potential recovery of 4.9% in 2021. Argentina’s much weakened growth potential after years of stagnation is very worrying as sustained economic growth and effective economic policies are necessary conditions for an enduring improvement of poor macroeconomic fundamentals.

Another sovereign debt default and debt restructuring

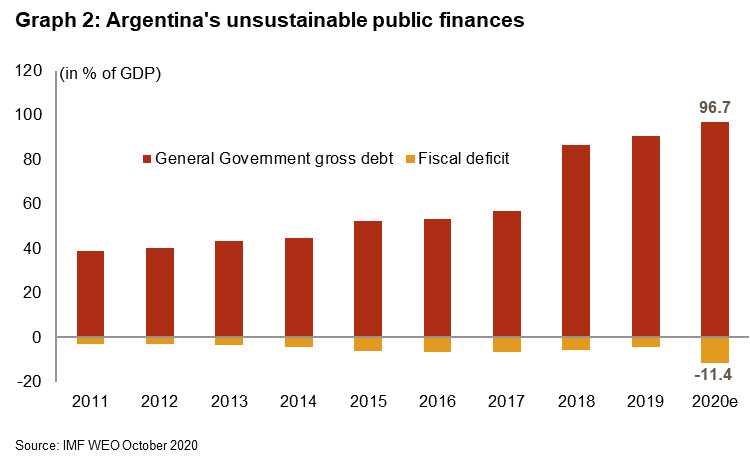

Given Argentina’s poor public finances, last May’s sovereign commercial debt default – exacerbated by the collapse of the peso, as more than two thirds of public debt is denominated in foreign currency – couldn’t be avoided. At the end of August, the government obtained private bondholders’ approval to restructure 99% of the USD 65bn of commercial debt, consisting of extended maturities and lowered interest rates. This positive milestone could ease external liquidity pressures. However, the general government debt stock is unchanged and is expected to rise above 95% of GDP this year. It remains unsustainable in the long term without a credible and effective stabilisation programme, fiscal consolidation and sustained economic performances. The Covid-19-related fiscal measures (about 6% of GDP) and fallen revenues are expected to widen the deficit substantially to 11.4% of GDP this year. A lower deficit is planned in the draft budget for 2021, thanks in particular to lower Covid-19 welfare payments, but this projection might have to be revised downwards in the event of a weaker recovery and a longer Covid-19 crisis.

Monetary expansion could remain a dominant tool used by the Central Bank to finance the fiscal deficit (combined with the issuing of debt denominated in peso) in the coming months, not only because of unpopular fiscal adjustments but also because there is still no access to financial markets. Those unsustainable fiscal and monetary policies will continue to harm consumer and business confidence by keeping the peso low – pushing up the public debt burden – and inflation at very high levels.

A major devaluation of the peso is probably looming

Since the currency crisis of August 2019, the peso has been under depreciating pressure in spite of the re-introduction and tightening of currency controls. During the first ten months of 2020, the peso lost an extra 30% against the US dollar, which it is fluctuating against within a crawling peg.

A sharp devaluation, though unpopular, increasingly seems inevitable in the near term. It would allow the huge gap between the official and parallel exchange rate to be narrowed and some confidence to be restored in a currency nobody wants any more. The tightened currency controls aimed at stemming the decline in foreign exchange reserves (used to stabilise the peso) and the peso slide continue to restrict the purchase of hard currency and hinder cross-border payment flows. They are unlikely to be lifted in the coming year until there is an improvement in the prospects for the peso and the reserves. Therefore, access to (official) foreign currency could remain difficult and uncertain, thereby continuing to erode business and investor confidence.

A misleading improvement in the current account balance

Together with the restructuring of sovereign debt to commercial creditors, the improved current account balance is the other seemingly positive economic event. However, in both cases, they reflect negative developments. Indeed, the current account deficit could turn into a surplus (from -0.9% to 0.7% of GDP) this year and grow to 1.2% in 2021 as a result of a sharper contraction of imports than exports. It is the consequence of weak domestic demand amid strict containment measures, the weak peso and the import substitution policy. This forecast is nevertheless uncertain as it will depend on how main exports evolve in a more uncertain global economy, the slow recovery of tourism and a rebound in demand from the country’s main markets such as Brazil and China. Moreover, with food (i.e. agribusiness) accounting for more than 45% of total exports, it is exposed to soft commodity price fluctuations and an increasing intensity and frequency of floods and droughts. Those vulnerabilities, including the lack of export base diversification, are a major constraint on generating the necessary receipts to repay a large external debt. Government plans to increase diversification could stall due to persisting economic policy and business environment uncertainties amid a difficult economic situation.

Uncertain outcome in ongoing talks with the IMF

A new IMF programme is essential for Argentina’s liquidity and for the government to present a comprehensive multi-year economic plan to boost an ailing economy, including bold fiscal adjustments which could help restore investor confidence (FDI has collapsed and portfolio inflows are in negative territory). Nevertheless, it is not on the cards, as the government is rather aiming for a deal with limited conditionality and a suspension of debt repayments to the IMF until 2024. This might even be too optimistic given the deepening recession and growing opposition within the Peronist coalition to a new IMF programme. That being said, the government is under financing pressure as borrowing from still reluctant and cautious private investors could remain locked for some time. Even though both the IMF and Argentina have an interest in a new financial programme, the final outcome is uncertain. What is certain is that the absence of any agreement would delay market access even longer, whereas a slightly binding programme would cloud the macroeconomic outlook with a persisting unfavourable investor climate and poor public finances and no guarantee that there wouldn’t be another default in the longer term.

As for the banking system, a major risk from US dollar withdrawals (at record levels after the currency crisis of 2018) has evaporated thanks to multiple exchange controls. The banking sector, starting from a rather sound position and characterised by dollarisation pressure on the back of poor peso confidence, is nevertheless harmed by a deepening economic recession and rising non-performing loans related to the Covid-19 pandemic. The longer the crisis, the more banks will see their position weaken.

External debt still too high to sustain in the LT

Argentina’s very high financial risk will worsen further in 2020 as a result of tumbled GDP and exports. Given the ongoing harsh recession, external debt – which was above 60% of GDP in 2019 – will rise further in 2020 and remain high in the coming years in the likely absence of a bold fiscal adjustment and strong economic growth. The recent restructuring of public commercial debt has left the external debt stock – three quarters of it public – intact and a chronic lack of current account receipts will complicate the authorities’ capacity to rein in external debt ratios and finance it in the MLT. The heavy short-term external debt accounts for a large part of the total stock and represents an additional weakness. Given investors’ persisting wariness of Argentinian external debt, even post-restructuring, debt roll-over via the markets is not (yet) possible. Therefore, besides the use of foreign exchange reserves, financing will have to come primarily from multilaterals and bilateral creditors. Now, the sharp cut (by USD 38bn) in debt servicing between 2020 and 2024 resulting from the debt restructuring will allow liquidity pressures to abate and buy time for Argentina. If the IMF also accepts a renegotiation of Argentina’s debt, the liquidity situation should improve further over this period. However, as from 2025, the debt service will increase sharply – as a result of the bond swap to postponed maturities – and financing gaps will arise again if market confidence is not fully restored and Argentina’s structural weaknesses are not tackled.

Foreign exchange reserves have been on a negative trajectory due to the overvalued peso, tumbled global demand and investment inflows. They shrank by almost 18% between September 2019 and September 2020. They are not sufficient to cover the short-term external debt. Their import cover might still be above 6 months due to the sharp decline in imports. Nonetheless, they are likely to remain under pressure as long as they are used for external debt payments and for defending the peso and as the export sector continues to suffer. On the other hand, while the bilateral local currency agreement with China (USD 18bn) has been extended for 3 years, the authorities will strive to keep reserves at adequate levels by further promoting import substitution and maintaining currency controls on purchases for imports.

MLT political risk downgraded to 7/7, and a negative outlook for the ST political risk rating

In this overall context of further increasing risks, Credendo has decided to downgrade Argentina’s MLT political risk rating to 7/7 (from 6/7). Moreover, the outlook remains negative for the ST political risk rating (6/7) amid tightened currency controls and rapidly declining foreign exchange reserves.

Analyst: Raphaël Cecchi – r.cecchi@credendo.com