Automotive sector: UK-EU trade deal negotiations add weight to a struggling British automotive sector

On 1 February, the UK woke up outside the European Union after a cohabitation of 47 years. Although the negotiations and the three postponements necessary to get there were difficult, we can expect future negotiations on the trade agreement between the two parties to be even harder to resolve.

What is the state of the British economy?

In 2019, the IMF estimated that real GDP growth in the UK would be 1.2%, slightly below the growth of the European Union (1.5%). For 2020, forecasts are improving slightly, with 1.4% growth for the UK and 1.6% for the European Union.

Since the exit referendum, the British economic context has become increasingly deleterious. Indeed, although the global slowdown and the Sino-American trade war significantly affected all economies globally, the uncertainties linked to Brexit (exit conditions, risk of a hard Brexit, tariffs on imports and exports, curb on immigration, disruption of the supply chain, etc.) added unnecessary weight to the shoulders of the British economy. The greatest concerns were related to manufacturing, such as the automotive sector. This negative context created, among other things, a sharp drop in investment in manufacturing in the UK (see graph 1).

When it comes to trade relations, the UK's main partner is the European Union, to which it exported 46% of its goods in 2018. Germany alone accounts for around 10% of UK exports. In comparison, and to further underscore the importance of the EU for the UK, the USA accounts for 13% of the UK's total exports. The main British exports include machinery and mechanical appliances, vehicles and parts, precious or semi-precious stones, precious metals, minerals, pharmaceuticals and electrical machinery and equipment (these sectors combined account for 57% of exported goods).

What will change in the post-Brexit transition?

The answer to this question is almost nothing. During this 11-month period, the two parties will negotiate the terms that will govern their relationship from 1 January 2021. Until then, European and British citizens will continue to be able to move freely between the different countries of the Union and the same will apply to goods. The UK will still be part of the single market, will continue to participate in the budget and will be subject to European legislation, although the country no longer has any political representation in official EU institutions. These 11 months are still a period of uncertainty for UK and foreign companies. In addition, since the UK is leaving a bloc with over 600 international agreements, the British government will have to renegotiate these treaties with these former partners.

Regarding the trade agreement with the EU, there is a wide range of possibilities between two extremes. One extreme would be a hard Brexit, wherein no trade deal is concluded by 31 December 2020 or the UK does not align with European regulatory and legislative requirements (comparatively equivalent to a hard Brexit). The other extreme would be that the two sides totally align. And between the two options there are infinite possibilities that affect the level of compliance by individual sectors. However, according to Sajid Javid, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, the most likely scenario would be a trend of non-compliance. A divergence from European rules would allow the UK to be more independent in terms of trade policy and to have more room to negotiate trade agreements with other countries (mainly the United States, their priority). It is a safe bet that if a trade deal is concluded with the USA, it will be necessary to make sacrifices on the trade deal with the EU, reducing access to the European market. The other side of the coin is that the further the UK moves away from European regulatory and legislative requirements, the higher the chances of facing tariffs for exporting to the EU. In addition, although concluding a trade deal with the USA, their second export market, is a priority, it will not be easy per se (and can only be performed after 31 December 2020). In fact, despite the wish of the British authorities to quickly conclude a UK-US deal, it should not be forgotten that the USA is unpredictable and that it has recently threatened the UK again to put tariffs on British car exports, because of their potential digital tax.

Focus on the automotive sector

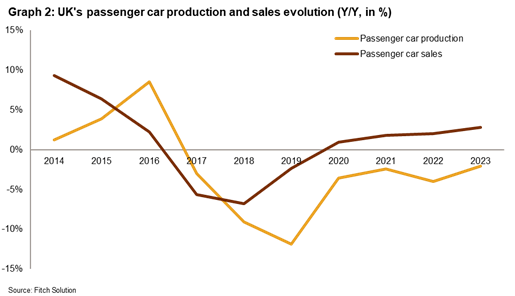

The UK is heavily reliant on the European car market; a total of 55% of cars made in the UK are sold in the EU (compared with 19% in the United States). Production and sales in the UK have been declining over the past three years, and Fitch Solutions (formerly known as BMI Research) forecasts that UK passenger car sales and production will have declined by 2.4% and 11.9% respectively in 2019 due to weaker household spending, lower investment in the manufacturing sector and subdued growth of the British economy.

Looking ahead, several threats weigh on the industry, including a Brexit without a trade deal (hard Brexit). Only a trade deal entailing full compliance with European standards could avoid trade and supply chain disruption. Otherwise, any differences will add costs to automotive manufacturers for export in the UK (tariffs, compliance tests, supply chain relocation, etc.), as well as for British-made cars to be sold in the European Union. For 2020, Fitch Solutions expects a further decline in passenger car production by 3.6% on the back of the falling rate of investment in the country, as carmakers hold off on non-essential capital expenditure until there is more clarity regarding the UK-EU trade relationship beyond 2020. Passenger car sales should turn positive but remain weak (0.9%, mainly because of the low reached in 2019, the lowest sales level since 2013), while car passenger production evolution is expected to remain negative until 2023.

Given the UK automotive sector's dependence on demand from the EU, EU-imported components and labour, a 'cliff-edge' Brexit would be severely damaging to the industry in the short term, and for up to five years, according to Fitch. The UK government could eventually redirect the industry towards other export markets and increase local content, but the drop in exports to the EU would be a large hole to fill. On the other side, given the complex and highly integrated supply chain within European countries, a hard Brexit would also impact the EU internally –7 out of the 10 top UK suppliers are from the European Union1 (and together account for 72% of UK automotive imports). Central Europe is also expected to be hit directly (Poland is the UK's 9th biggest supplier, while the Czech Republic is the 11th biggest) and indirectly, since they are very reliant on Germany, as could be seen during the manufacturing slowdown that started in mid-2018 and affected Slovakia and the Czech Republic in the first half of 2019.

Another threat weighing on the UK's automotive industry is a potential trade deal with the USA after 2020. Since the current 10% tariff on imports of US cars could be removed, the UK market could become flooded with American-made cars, such as the highly successful SUV, which has already gained market share in Europe, lowering demand for domestically produced cars. Furthermore, as stated above, any trade deal with other countries with different standards could lead to reduced access to the EU for UK-made cars. Finally, due to the Japan-EU Free Trade Agreement, tariffs between the EU and Japan have been removed on car exports. If an agreement – or lack thereof – between the UK and the EU were to result in export tariffs, it is a safe bet that Japanese companies would repatriate their production so that they could export more easily to the EU.

Conclusion

At the dawn of negotiations between the UK and the EU, we can safely say that the risks linked to Brexit are real. Depending on the type of trade agreement concluded, there may be very significant consequences for the entire UK automobile industry, and this would have repercussions throughout Europe. The possibility of a hard Brexit cannot be forgotten because this risk is real, and perhaps even underestimated. Meanwhile, this uncertainty continues to have devastating effects on the British economy. And as Sajid David has admitted, there will be winners and losers.

Analyst: Matthieu Depreter – m.depreter@credendo.com

1 Germany, Belgium, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Italy and Poland (in 2018, in value) according to UN Comtrade