Egypt: Downgrade from category 5/7 to 6/7 for medium- to long-term political risk

Highlights

- As a food and oil importer, Egypt has been hit hard by the fallouts of the war in Ukraine.

- High reliance on capital flows is a key vulnerability amid tightening of global financial conditions.

- Public finances are weak given the high debt and high interest payments compared to public revenue.

- The announced IMF programme is positive news, but significant downside risks remain given Egypt’s imbalances and the current global economy.

Pros

Cons

Head of State

Head of Government

Population

GDP per capita

Income group

Main export products

Downgrade of the MLT political risk rating from category 5/7 to 6/7

Egypt’s macroeconomic situation improved substantially in the years preceding the Covid-19 pandemic. The implementation of a reform agenda under a three-year IMF programme (2016-19) allowed Egypt to stabilise its macroeconomic situation, gradually consolidate its public finances and avoid a balance of payments crisis. As a result, the MLT political risk was upgraded to category 5 in 2019. However, despite these improvements the country still faced significant vulnerabilities that were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and fallouts from the war in Ukraine. These shocks renewed pressure on Egypt’s fiscal and external balance and the risk outlook for the country has consequently deteriorated. As a net food and oil importer, Egypt has been hit hard by the sharp increase in commodity prices. Moreover, its reliance on foreign capital financing and its weak public finances create a dangerous cocktail in a context of sharp tightening of global financial conditions. Last but not least, the net international investment position has deteriorated gradually over the last decade and is expected to deteriorate further amid the IMF support programme and other loans for bilateral and multilateral creditors.

Sustained growth levels hide important macroeconomic imbalances

Egypt weathered the shock of Covid-19 fairly well, and was one of the countries that only experienced an economic slowdown in FY2020. In addition, Egypt’s economy is projected to grow rapidly in FY22/23 and sustain important growth rates in the medium term amid state-led infrastructure and energy projects. Despite the sustained growth rates, however, important imbalances persist. Key vulnerabilities linked to Egypt’s economic model include its small export sector, low savings and investments, low productivity and high informality within the economy. Furthermore, the heavy presence of the state in the economy represents a key structural imbalance, and this prominent role has been linked to low levels of foreign direct investments (FDI) and to hampering private sector development. A business environment that is more conducive to the private sector is considered as paramount for higher and more balanced growth. This is one of the objectives of the recently approved IMF programme. On several occasions, Egyptian authorities have expressed their willingness to privatise part of the economy, but given vested interests, introducing the reforms necessary to foster the private sector is considered very challenging.

Public finance vulnerabilities exacerbated by Covid-19 and significant fallouts from the war in Ukraine have impacted the Egyptian economy

Prior to Covid-19, the reforms under the IMF programme and the sustained growth levels were putting public debt levels on a more sustainable path – for instance, after peaking at 97.8% of GDP in FY2016/17, the public debt burden decreased significantly, reaching 80% of GDP after only two years. Yet despite continued consolidation efforts – a positive primary balance since FY2018/19 and an expected gradual decrease in public debt (to 86% of GDP in FY22/23) –, interest payments to the public revenue ratio remain very high: 43% in FY2022/23, the fourth largest in the world (after Sri Lanka, Ghana and Pakistan), and it is expected to remain high in the coming year. The huge interest burdens have been attributed to the monetary policy pursued until this year to attract capital inflows, which pushed interest rates among the highest in the world, and as Egypt’s public debt is largely financed domestically, this led to very high interest payments. A partly mitigating factor is that a large share of public debt is denominated in local currency and it is financed largely by the domestic financial system. This also implies that the banking sector is heavily exposed to the public sector, thus any restructuring of the domestic public debt would inevitably hit the banking sector and its ability to support the private sector.

Egypt has been running consecutive current account deficits almost interruptedly for more than a decade

One of Egypt’s main structural vulnerabilities is its limited export sector. The country is reliant on private transfers (46.6% of current account receipts in 2021), tourism (13.1% of current account receipts in 2021) and revenue from the Suez Canal (transport accounted for 12.6% of current account receipts in 2021) as a source of foreign exchange receipts. The Covid-19 pandemic and the fallouts from the war in Ukraine on global food markets and commodity prices have put pressure on Egypt’s current account balance. And as a net oil1 and food importer and a top wheat importer, the North African country has experienced significant import bill pressures as a result of the commodity price surge provoked by the war. Its direct dependence on Ukraine and Russia for wheat imports and for the tourist sector has added to the country’s woes – to finance its structural current account deficit, the country relies on foreign capital inflows. Following global investors’ flight to safety in the light of the war in Ukraine and the ongoing tightening of global financial conditions, Egypt has experienced large capital outflows. These events have led to a fall in foreign exchange reserves to under three months of imports (cf. graph).

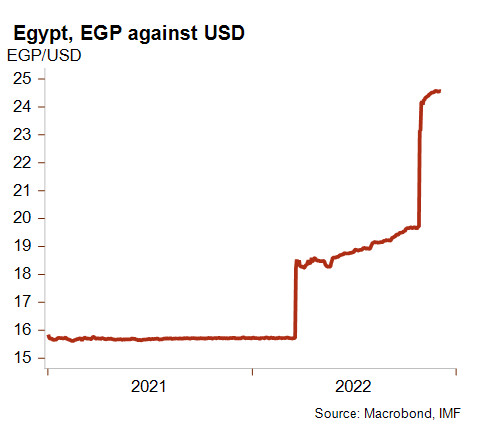

Moreover, the Egyptian pound has depreciated sharply against the dollar (cf. graph, the rising line represents depreciation). In the short term, the depreciation would add to inflationary pressures (16.2% YoY in October) and increase the cost of reimbursing debt denominated in foreign currency in local currency terms. Nonetheless, the depreciation is in line with the IMF requirements of a more flexible exchange rate, and it is expected to ease pressure on foreign exchange reserves. It is worth noting that this was also an objective under the previous IMF programme, but the authorities de facto abandoned it. On a positive note, the IMF approved a 46-month Extended Fund Facility arrangement of USD 3 billion. The IMF programme is also expected to attract additional financing from regional partners and multilaterals. However, while positive in the short term, these new loans add to the external debt burden, which is currently at a moderate level.

The IMF arrangement is key to alleviate liquidity pressure

The approval of an EFF support programme by the IMF Board of Directors is very positive news, as it would alleviate Egypt’s liquidity pressures (see the graph showing a sharp drop in foreign exchange reserves) and allow authorities to phase out the mandatory use of letters of credit for import finance. This would also be good news as the restrictions – that aimed to reduce the imports – are leading to undue payment delays in cross-border trade transactions. Without a lifting of the restrictions and in case of further pressure on foreign exchange reserves, Credendo is likely to downgrade its short-term political risk classification to category 6.

Analyst: Andres Hernandez Cardona – a.hernandezcardona@credendo.com

1 Based on WDI figures, Egypt was a net fuel exporter in 2021 (while being a net importer in the 2012-20 period).