Climate change: An extreme El Niño is on the cards, potentially impacting sector and country risks in different ways

Highlights

- After three years of cooler La Niña weather, an extreme warm El Niño is on the cards for 2023 and 2024.

- The effects of El Niño differ between regions and seasons, with some regions likely to experience droughts while others more rainfall.

- Every El Niño is unique, making its implications difficult to forecast.

- The impact of El Niño will be most visible in the agriculture, infrastructure and electricity sectors.

- El Niño could impact country risk through higher social unrest and political violence, tighter monetary policy, and deteriorating public finances.

El Niño is back after a 3-year pause, and is expected to impact weather across the world

In late May, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared that the El Niño weather pattern had officially arrived, is likely to be extreme, and will persist till 2025. El Niño is a meteorological phenomenon that occurs at irregular frequencies of two to seven years, and triggers extreme weather events throughout the world. The return of El Niño is no surprise after three years of cooler La Niña weather, as typically the Pacific Ocean naturally cycles between El Niño and La Niña conditions. However, its potentially high intensity could have wide repercussions. The consequences on the climate in different regions of the world will vary, even within the same country, while several climatic factors make each El Niño unique. Hence, forecasting the impact of this upcoming El Niño is extremely difficult. In general, during El Niño years, the south of the USA experiences a cooler and more humid climate, while the mid-west of the USA (corn and soybean belt) is hotter and drier. It also incites droughts in Central America, northern Brazil, Colombia, India, Australia, South Asia and Africa, and increases the risk of extreme typhoons in the Pacific Ocean. On the other side of the world, in the North Atlantic, El Niño could theoretically decrease the risk of fierce hurricanes, but the current very warm ocean water in that region could counterbalance that effect. On the upside, the weather pattern is expected to bring more rainfall in the Horn of Africa and South America; both regions having suffered from intense droughts in recent years. That being said, it could expose some regions to flood risks (e.g. Peru, Ecuador), and there is no conclusive correlation when it comes to European weather. Last time there was an extreme El Niño year (2016), heat records were broken all across the world, including in Europe. Indeed, an extreme El Niño can be expected to exacerbate global warming in the coming two years. The effects of El Niño will vary by geography and season, but its impact will be most apparent in the agriculture, infrastructure and electricity sectors relying on hydropower. Below is a non-exhaustive list of commodities expected to be impacted by El Niño, keeping in mind that the impact of El Niño on commodities can vary depending on the region and local agricultural practices. *

- Rice

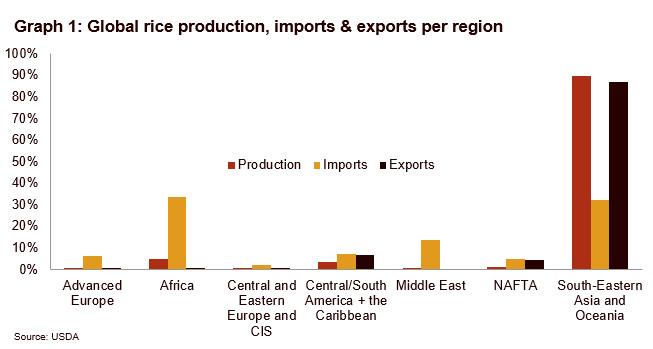

The biggest rice-producing region, with 90% of global production, is South-East Asia and Oceania – China and India’s production alone accounts for 61% of regional output. Therefore, the expected low rainfall levels will impact rice yields. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) says that, during previous El Niño events since 2000, rice yields dropped by 4% to 11% from the normal trend. This could potentially lower regional output and therefore increase the risks of food shortages and higher prices. In the case of shortages, we could expect the producing countries (China and India) to impose export restriction measures in order to stem domestic inflation. Indeed, despite being the leading global producer, China is also the leading global importer of rice at a country scale. The imposition of export bans would further fuel food inflation, above all in importing countries, and hence could trigger social unrest. Regarding imports, this year Africa became the first global regional importer of rice (33% of the global volume) and could be under heavy pressure if yet more food shortages or price increases occur. Nigeria imports 12% of that 33%, followed by Ivory Coast and Senegal (9% and 8% respectively).

- Corn and soybean

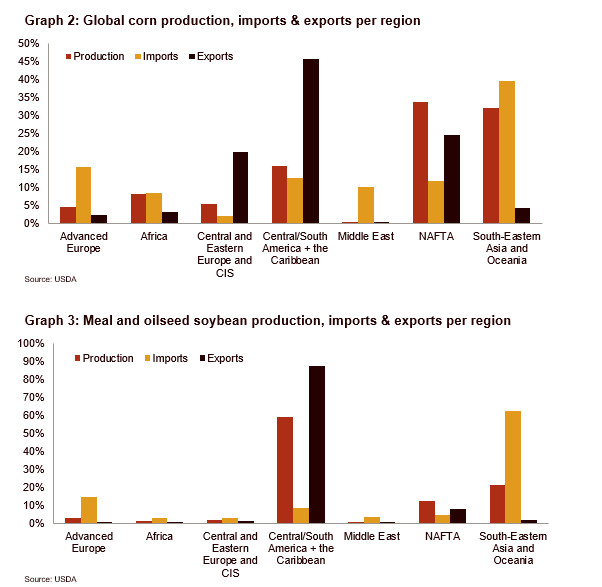

Corn and soybean have had a similar pattern in terms of production and trade. Although NAFTA leads global corn production at 34%, closely followed by South-East Asia and Oceania – and China accounts for 75% of that – it is not the biggest exporter, given that Central & South America accounts for 46% of global corn exports (Brazil accounts for 69% and Argentina 27% of regional exports). For (meal and oilseed) soybeans, production is concentrated in Central & South America, and South-East Asia and Oceania (59% and 21% respectively). Central & South America accounts for 88% of global exports (Brazil accounting for 77% of regional exports) and imports are concentrated in South-East Asia and Oceania (62% of global imports, dominated by China, which accounts for 70% of those imports).

Indeed, China relies on corn and soybean imports to feed its huge meat sector. Therefore, more rainfall in South America could impact yields and decrease regional corn production. The effects along the supply chains could be broad, but we can highlight the inflationary effect it could have on the meat sector in China, specifically for pork production. China could be forced to purchase soybeans and corn elsewhere (e.g. the USA), driving prices higher in these regions. Conversely, rainfall could ease conditions for soybean farmers in Argentina and in Brazil, given that it could boost harvests after intense droughts. This could also mitigate the consequences of the lower corn harvest on the agribusiness supply chain.

- Coffee

The consequences for the coffee market could also be significant. Coffee is mainly produced in South America and South-East Asia. Arabica production represents 55% of global production and is mainly produced in South America (78%, 60% of which in Brazil). The other, Robusta, is mainly produced in South-East Asia and Oceania (59%, 65% of which in Vietnam). The upcoming El Niño is therefore expected to reduce output in Vietnam and Indonesia, according to Fitch Solutions, as was the case in 2016/2017 in Vietnam, when El Niño led to a decline in output in these countries, resulting in an almost 10% fall in global production. In Brazil, which produces two times more Arabica than Robusta, current production is already impacted by the drought and the next production could also be hit. Indeed, the biggest coffee-growing regions are located in the south-east of the country, where El Niño tends to bring drier conditions, leading to lower yields that cannot be compensated by improved yields in the northern region (Rondônia). Globally, demand will shift from Arabica to Robusta, which is less expensive. The consequences on the price of Robusta are visible on the market: prices for Robusta have increased by 18% in the last three months. This price increase should cap the growth in demand for coffee, mainly in developed regions.

- Sugar

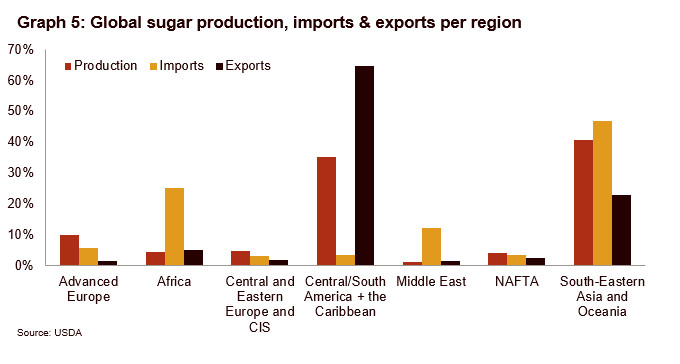

The two biggest global producers of sugar are South-East Asia and Oceania (mainly India) and South America (mainly Brazil), and they are also the biggest exporters. The El Niño event is set to reduce yields and output in India because of droughts, while heavy rains could slow down the sugarcane harvest in Brazil. The EU could also be impacted by higher temperatures and droughts. Therefore, global output could be revised down in the coming months, pushing up sugar prices.

- Other commodities

Other commodities could be hit by El Niño and see price increases. For example, palm oil produced in Indonesia and Malaysia (93% of global supply), fresh apples, cotton and fresh peaches and nectarines, mainly produced in South-East Asia and Oceania (60%, 55% and 71% of global production respectively); fresh oranges and orange juice, mainly produced in Central/South America and the Caribbean (36% and 68% respectively). The meat sector could also be impacted by lower feedstock and pasture availability, reducing the sector’s productivity, while the aquaculture sector could be hit by higher sea temperatures, creating conditions for disease transmission.

- Infrastructure

Drier weather in Panama could temporarily hurt international trade, given that 6% of maritime trade passes through the Panama Canal. There have been already weight constraints on Panama Canal operations, and the issue is likely to become more acute in 2024. In general, infrastructure is also often affected by the more extreme weather events triggered by El Niño, such as fiercer typhoons, floods, wildfires, etc. Lastly, electricity – especially in regions reliant on hydropower, such as South America and China, could be upended by local droughts, driving up energy prices.

- Prices

Commodity prices have therefore been strongly influenced by announcements related to the very likely appearance of El Niño in the coming months, depending on the region. Spot and future commodity prices have already risen sharply, based on weather estimates for the targeted regions. However, a change in these forecasts could still have an upward or downward impact on these prices. When we look at the prices of impacted commodities, we see disparities between soft commodities and grains/oilseeds. Indeed, the latter are historically high due to geopolitical uncertainties linked, among other things, to the Black Sea Grain Initiative. The El Niño effect therefore only took over at the end of May, while for softs the upwards trend since the beginning of 2023 is clear, despite a recent fall in sugar prices following the better-than-expected Brazilian crop this year.

El Niño can impact country risk

Central/South America and the Caribbean, together with South-East Asia and Oceania, dominate the production of key agriculture commodities. As a result, El Niño could have a big impact on agriculture production, could hit economic performance, push up prices and – in a worst-case scenario – lead to food shortages. As a result, El Niño is likely to trigger more social unrest, as we have seen in the past (e.g. the Arab spring in 2010, tortilla protest movement in Mexico in 2007, food riots in sub-Saharan Africa in 2007–2008). Moreover, extreme weather events such as droughts and floods can undermine economic livelihoods and increase poverty and wealth inequality, while poverty and wealth inequality have a significant influence on political violence and conflicts. Indeed, regions hit by an extreme El Niño could face higher political violence as a consequence.

Higher food and energy inflation can also impact monetary policy. All across the world, the potentially higher inflation in the coming two years could lead to more restrictive monetary policy for longer, or even to further monetary tightening. This is especially the case in the context of heightened geo-economic fragmentation and increased rivalry between China and the USA, which might also push up prices. Higher interest rates and/or lower lending could hurt companies and hence the business environment risk.

Lastly, El Niño could also hurt public finances. First of all through higher lending rates, if monetary policy remains tight over a long period. Secondly, to stem inflationary pressures, some governments might decide to impose trade restrictions, cap prices or adopt some fiscal measures (e.g. subsidies). Thirdly, public finances could also be hurt through weakened government revenues after being hit by extreme weather events triggered by El Niño and heightened spending to finance damages. In this context, a rise in protectionism and a (further) deterioration of public finances in some countries are possible in the coming years.

Analysts: Jolyn Debuysscher – j.debuysscher@credendo.com; Matthieu Depreter – m.depreter@credendo.com

* All data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) refer to the 2022/2023 marketing year, except for coffee and rice, for which 2023/2024 data are available.