Climate change increases social-political and geopolitical risks in the medium to long term

Highlights

- Climate risks are accelerating as GHG emissions keep rising and large emitters are failing to take bold actions to reduce them.

- The impact of climate change on MLT country risks goes well beyond economic risks.

- Climate change will increase political violence, social unrest and geopolitical risks.

- Rising food insecurity and water stress will increasingly lead to mass migration and conflicts.

- All countries will be hit hard but unevenly as climate change is expected to affect country risks the most in low-income countries.

Multiple climate risks stubbornly on the rise

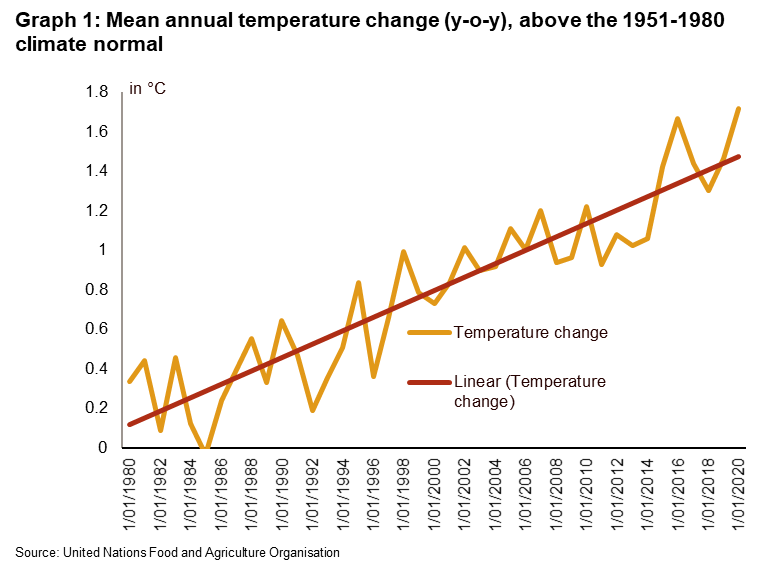

While the world continues to be distracted by the Covid-19 pandemic for the third successive year and is now facing an energy crisis exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the climate change disaster, a risk of unprecedented scale and complexity, is more evident than ever. Graph 1 shows the clear rise in surface air temperature measured over global land area since 1980, with 2020 showing a record 1.7 degrees Celsius above the 1951-1980 climate normal. Climate change is affecting many countries, particularly the least resilient low-income ones, through an increasingly intense impact on their environment and population. Its acceleration – boosted by the still rising GHG emissions – means that the severity and frequency of climate change impacts will speed up as well, thereby clouding the MLT outlook of all countries.

Climate risks can take multiple forms. Physical risks are the most important ones1 and consist of more extreme and frequent natural disasters, rising sea levels and higher average temperatures affecting all dimensions of ecosystems and human societies, such as water supply, agriculture production, food security, economic activity, people’s economic livelihood, the fishing sector (notably due to ocean acidification) and biodiversity. While climate risks are currently being evidenced predominantly by severe droughts, floods, water stress, heatwaves, wildfires, hurricanes and typhoons, the rapid decline in biodiversity is also of particularly great concern given its systemic central role in ecosystems and thus for humanity. Moreover, in the context of Covid-19, scientific research has highlighted the high risk that climate change will facilitate the emergence and spread of new pandemics in the future. It could occur indirectly, through extreme natural disasters, damage to ecosystems and migration, and through some of its causes, like deforestation, which brings humans and wildlife ever closer. Now, following a decade of record temperatures and the UN COP26, which saw the largest carbon emitters fail to make the bold commitments required by the climate change challenge, it is appropriate to address to what extent MLT country risks will be shaken by the acceleration of climate change.

Climate change has clear economic and other impacts

In the long term, within an increasingly shrinking timeframe, climate change will greatly impact the global economy and country risks. In a past publication, the impact of extreme natural disasters on the very vulnerable small Caribbean and Pacific islands and the gradual economic impact of droughts was analysed. At country level, the vulnerability caused by affected domestic production, commodity and food exports, public finances (weakened government revenues and heightened spending to finance adaptation costs and natural disaster-related damage) and external debt will have a particular impact on the effects of climate change. Besides those vulnerability indicators, as used in Credendo’s MLT country risk assessment model, it has to be emphasised that there are crucial non-economic aspects as well that need to be taken into account and that weigh on the medium-/long term-country risks.

Climate change affects poverty and inequality, fuelling political violence

Political violence risk is driven by various factors including availability of weapons, ethnic and religious tensions, wealth inequality, institutional resilience and a high level of distrust vis-à-vis of the authorities. Climate change has increasingly been influencing many factors that contribute to political violence. Extreme weather events can undermine economic livelihood (e.g. destruction of crops, machinery and homes, reduction in quality of grazing lands) and increase poverty and wealth inequality between groups that are affected by the extreme weather events and those that are not. In all regions, poverty and wealth inequality have a significant influence on political violence. Desertification has also been regularly linked with increasing political violence, for example in the Sahel region of Africa. In Mali, in recent decades, drought periods have occurred more frequently, placing greater stress on a country with weak political institutions as well as religious and ethnic tensions. Moreover, the link between political violence and inequality is even stronger if the situation deteriorates rapidly (such as after a natural disaster). The impact will be most acute in low-income countries where food still accounts for a large share of the population income, but also in middle-income countries, notably due to income inequality.

Climate change affects food security and water availability

Climate change can also cause political unrest because of higher food inflation and food insecurity. For example, huge droughts in South and North America in 2021 have led to sharply rising sugar, wheat and oat prices (see graph 2). In the past two decades higher food prices have been clearly linked with unrest, as illustrated by large food protests in Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. food riots in a dozen countries in 2007-08), Latin America (tortilla protests in Mexico in 2007) and the Middle East. In many low-income countries with mostly poor populations, social protests have increased the pressure on governments, sometimes led to political changes and even contributed to some extent – together with other factors – to fuelling civil conflict (e.g. the Arab Spring). Lower yields and higher prices could cause food insecurity in less resilient, food import-dependent countries, triggering political violence. Looking ahead, besides Africa and the Middle East, climate-related social risks fuelled by food insecurity and inflation are also expected to be high in Latin America, where agriculture – which is under threat – is a major source of income and income inequality is very high.

Climate change will also create scarcity of resources such as water. Fresh water is increasingly in short supply, with nearly two thirds of the global population living in water-stressed conditions. Climate security risks can already be observed in several countries and regions, primarily in Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. terrorism in the Sahel, violence between farmers and herders in Nigeria, ethnic conflicts in Kenya) and in the Middle East. They occur in those regions because the populations are poor, land fertility is decreasing and water stress rising. As a matter of fact, and as has often been seen in history, declining water supply promises to be the number one factor driving future conflicts within a country and between countries. The Middle East region (e.g. Iraq, Syria, Jordan) is emblematic of such a risk, as its water supply will become more instable and could even decrease in many areas to levels where human life is no longer possible. Other well-known examples of conflict risks come from the ongoing dispute between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, claimed ownership by China of Tibet’s waters (meaning that it would be the upstream controller of most of South Asia’s biggest rivers), and Turkish dams on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers creating tensions with Iraq and Syria.

Climate change will trigger mass migration

Conflict and social instability risks will also be fuelled by mass internal and external migration flows of historic scale, triggered by climate change. The rising sea level is threatening people’s living in the medium term in atoll islands in the Pacific ocean. Furthermore, research has shown that humans have been living in a narrow temperature span (11°C-15°C) for over a thousand years. Hence, global warming is leading to more and more land and areas becoming almost or completely unliveable for humans. Therefore, the World Bank predicts that at least 200 million refugees (a figure probably much underestimated as research shows that for every degree by which the earth warms up, about a billion people will come to live in unliveable land), principally from poor regions – nearly half in Africa, followed by East and South Asia – will be forced to migrate by 2050. Those mass population movements will put a lot of stress on societies and create huge social and political tensions within them. Struggles between hosts and newcomers can erupt especially when there are scarce resources in the host region or country. Migration in a context where many potential conflict factors already exist (e.g. high poverty, weak institutions) in the host country or region can especially act as a trigger for political violence. Syria is a good illustration. Between 2006 and 2010, a drought transformed almost 60% of the country into desert and, by 2009, may have killed as much as 80% of cattle. A mass movement of farmers to the cities, in combination with the inability of institutions to handle the migration flow and existing ethnic tensions, were the catalyst for the civil war. Moreover, given the gradual rise of the far right, increase in autocracies and populism in Europe – a top destination for cross-border migrants, especially given that the region is expected to be proportionally the least affected by climate change – political and social tensions will rise. Besides social and conflict risks, mass migration threatens to cause health crises in transit and destination countries.

Climate change will impact the geopolitical powerplay

Climate-related conflict risks will also take the form of geopolitical risks. In association with rising climate risks in a currently emerging new global order with scarcer natural resources, geopolitical risks are likely to increase between superpowers and with or between emerging powers. Those risks will also hit many countries that are strategically (e.g. Pakistan) or involuntarily involved in the geopolitical games. When it comes to energy transition, geopolitical competition will certainly be fierce in the future (e.g. in the Arctic), will probably reshape the global order and will favour economies producing and exporting those precious commodities. However, because of the stress it will place – together with the demographic burden – on resource scarcity, climate change will also trigger a race (that has already started) for vital natural resources such as fish and land on which to grow cereals, rice, etc. While China is ahead in this race to ensure food security and internal stability, Russia as well as emerging powers such as India, Turkey and Saudi Arabia are already very active, notably in Africa.

Risks will materialise worldwide, with country and regional disparities

Political violence is thus likely to be a growing threat boosted by the acceleration of climate change. Social unrest is likely to be more frequent, with more competition for natural resources, leading to greater political instability and uncertain government policies. When climate risks are assessed, it is important to remember not only that climate change will affect all countries in the world, but also that reaching climate tipping points2 will exacerbate climate and country risks worldwide. There is nevertheless great scientific uncertainty about the size of their natural and economic impact and about the interactions of those natural upheavals. That being said, the impact of climate change will be felt unevenly and in different ways, due to geographical factors and just as importantly because of economic, political, social and ethnic dimensions. In general, developing countries are often associated with high poverty levels and low incomes, meaning that resilience to climate change disaster is and will be structurally constrained and will facilitate socio-political and conflict risks. At regional level, Africa, followed by Asia, the Middle East and Central America, are seen as the regions most vulnerable to climate change disaster.

Analysts: Jolyn Debuysscher – j.debuysscher@credendo.com; Raphaël Cecchi – r.cecchi@credendo.com

1 Transition risks related to the shift to a decarbonised economy (particularly acute for fossil fuel-dependent countries) are other types of climate risks that will be assessed in a future publication. 2 Such as shifts in atmospheric circulation, thawing permafrost, weakening carbon sinks (forests and oceans), ice sheet disintegration and Amazon forest switching from rainforest to savannah, which will bring about irreversible changes.