Bangladesh: The forced resignation of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina paves the way for a challenging and uncertain political transition

Highlights

- Landslide student-led protests during the summer resulted in the forced resignation of long-serving Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who was abandoned by the army.

- An uncertain political transition will be run by an interim government headed by economist Muhammad Yunus until elections are held.

- Time will tell whether Bangladesh is to enter a new political era or whether traditional parties will maintain their political dominance.

- Challenges are elevated at a time of economic slowdown and currency and liquidity pressures, which affect a difficult business environment.

- The outlook is negative for ST and MLT political risk ratings.

Pros

Cons

Head of State

Head of Government

Population

GDP per capita

Income group

Main export products

A turning point or a pause in Bangladesh’s recent political history?

It’s been a hot political summer in Bangladesh, marked by landslide mass student-led protests following a controversial public job quota system. Violent army repression and the population’s rising opposition to the Hasina government’s rule eventually led to a political earthquake. After holding on to power for 15 years, PM Hasina was abandoned by the army and forced to flee to India on 5 August. Major decisions were then quickly taken to restore calm and move forwards in the political transition, particularly upon demands made by the students. The President dissolved Parliament, numerous political prisoners were freed and the ban on the largest Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami was revoked. Meanwhile, an interim government with members drawn from across civil society was formed to run the country until elections are held, headed by economist and former Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus (opposed by former PM Hasina).

The latest events bring hope to the country given the autocratic trend of previous years and wide repression across the media and political opponents, among others. This could be a turning point in Bangladesh’s political history, but this will depend on how the current transition evolves and is managed, as several headwinds are predicted to hinder the smooth transfer of power and a fundamental change in political direction. In this regard, the timing of the elections is significant. According to the Constitution, elections should be held at the latest three months after Parliament’s dissolution, so in this case early November, which appears to be impossible and not desirable. Indeed, in just a short period of time, the interim government wants to clean up a political system long dominated by the two major dynasties of the Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh National Party (BNP). Ideally, Bangladesh also needs fresh faces and a new political landscape, which is a long way off. If the opposition BNP were to win the elections, political practices are likely to remain largely unchanged. Despite the hopes of a new political era, especially called by students, entrenched political interests will represent a major obstacle to deep structural reforms. Moreover, Yunus’ inexperienced interim government will face potential political revenge temptations from both sides of the spectrum, AL and BNP, which will make it even more challenging. Therefore, the coming months will be tense. The shorter the transition, the more likely it is that traditional political parties continue to dominate the political landscape, while the longer the transition, the higher the instability risks. Realistically, it will be a while before the next elections are held.

Political shock amid a weakened economy

The current political turmoil is happening at a time when the domestic economy has been struggling against adverse external developments. Real GDP growth has slowed over the last two years, from 7.1% in FY22 (ending in June) to 5.4% in FY24, most notably due to reduced export growth hit by a weakened global economy, particularly the key Western demand for the dominant garment sector (accounting for 90% of goods exports). In the short term, the sector could suffer from political uncertainty and hesitant investors, while the social context also remains difficult and a burden for the interim government with the persisting high cost of living highlighted by elevated price inflation (especially in foodstuffs), which has surged above 10% year on year since July 2024.

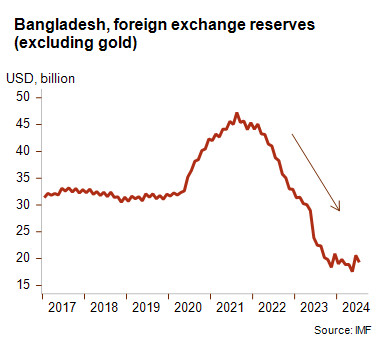

The taka (-40% against the US dollar since August 2022) and liquidity remain under pressure, although the steady decline in foreign exchange reserves somewhat stabilised between January and July 2024. Still, Bangladesh’s liquidity was weakened by the 60% drop in foreign exchange reserves since August 2021, lowering the current import cover to 2.5 months instead of 7 months in 2021.

This has affected Bangladesh’s financial risk profile, even though external debt ratios remain at sustainable levels (forecast at around 23% of GDP in FY24–25). The collapse of foreign exchange reserves has been explained by the increase in debt servicing, the exchange rate policy – namely, the Central Bank’s interventions to defend the taka – and capital outflows. To counter this negative trend, since FY23 the authorities have reverted to import compression, which has enabled the current account deficit to remain close to balance. Bangladesh can also count on IMF support by means of a financial programme approved in January 2023. However, future capital inflows will depend on the fragile political situation and a reduction in uncertainties.

Economic policy challenges against a negative outlook

Weak institutions, high levels of corruption, a volatile power supply and red tape are also factors that are harming investor attractiveness and the business environment risk (the current rating being E/G). These factors will have to be tackled by the next administration if Bangladesh wants to elevate foreign direct investment from low levels and improve the business climate. Boosting economic diversification will have to be addressed as well to mitigate the long-term high reliance on the garment sector. Public finances represent another downside risk to monitor due to very low government revenues, of which about 20% are allocated to interest payments, and in spite of a slight surge in GDP to 8.7% in FY24, low revenues continue to constrain the country’s future fiscal space. The fiscal deficit has nevertheless been well contained in recent years at around 4.5% of GDP, slowing the increase in public debt where the ratio was expected to reach a moderate 41% of GDP (albeit at a high 475% of government revenues) in this financial year. It now remains to be seen whether fiscal discipline will be preserved during the political transition. Meanwhile, the poor health of the banking sector is another concern, particularly for state banks with insufficient capital and non-performing loans above 20%. Moreover, prolonged political uncertainty could delay much-needed banking reforms. Last but not least, Bangladesh is among the most vulnerable large countries when it comes to climate change and rises in sea level, and the country is increasingly hit by severe cyclones and floods that harm livelihoods, agriculture and food security. Therefore, this huge risk must be made a high priority in the to-do list of any future government.

Given the challenging and uncertain political and economic situation, Credendo has a negative outlook for its ST and MLT political risk ratings, currently both at 4/7.

Analyst: Raphaël Cecchi – r.cecchi@credendo.com