India: Slowing economic recovery

Highlights

- After the Covid-19 pandemic, inflation is another external headwind impacting economic activity.

- High commodity imports have widened the current account deficit and sent the rupee to record low levels.

- An active trade policy in Delhi, which allows for a sharp increase in Russian oil imports, has helped to limit the negative economic impact.

- GDP growth is on a gradual decelerating trend, which is expected to last for the next two years.

- The stable outlook of country risk ratings is under pressure.

Pros

Cons

President

Prime Minister

Population

GDP per capita

Income group

Main export products

Inflation clouds the economic outlook

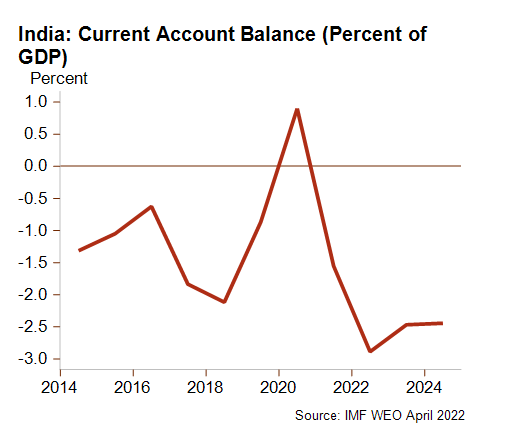

The Indian economy has had to cope with new external hurdles, and after the severe shock of Covid-19 in 2021 and a weaker third wave in early 2022 it must now confront the global inflation shock. The war in Ukraine and the resulting inflation wave have hit the Indian economy hard through higher food and energy prices, and energy price inflation is particularly acute in India because the country relies heavily on fuel imports. As a result, inflation has been above the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) 2–6% target since May, but fell slightly to 6.7% in July. This higher level can be explained by costly fuel imports – accounting for nearly 30% of total imports in 2020 – that have significantly widened the current account deficit. The exceptional surplus of FY2020 turned into deficit (-1.6% of GDP) in FY2021 (as at March 2021) and last April was forecast to almost double to a ten-year high of -3.1% of GDP in FY2022.

The prospect of persisting high energy prices – in spite of a slowing global economy – will keep the deficit in deep seas for a protracted time. This also means that this year and the next, the Indian rupee may depreciate further from its current historic nadir vis-à-vis the US dollar. For the first eight months of this year the currency remained on a downward trend, falling by 6.7%, a negative trajectory that can be explained by the sizable current account deficit, rapid US interest rate hiking and high Indian public debt. This inflationary context is affecting private consumption and manufacturing production. Moreover, the RBI has been tightening its monetary policy by means of several interest rate increases between May and August (from 4% to 5.4%), and further increases and a tight monetary policy are likely as long as inflation remains above the RBI inflation target band.

These developments are inevitably slowing down the economic recovery that followed the pandemic shock; GDP growth is thus expected to fall gradually from 8.7% in FY2021 to 7.4% in FY2022 and 6.1% in FY2023. In such circumstances, as private consumption is traditionally a key growth driver, controlling inflation and dealing with the risk of stagflation are top priorities for PM Modi. In response, Delhi decided to ban wheat exports (with a few exceptions) last May and subsequently to also limit sugar shipments. Moreover, Delhi has been actively working on its foreign trade policy by negotiating future free trade agreements (UK, EU and Australia) and strengthening its trade ties with Russia. The government has clearly benefited from its strategic neutral stance in the conflict in Ukraine since it has managed to limit energy shortages – although many Indian industries have nevertheless been hit by gas shortages – and buy vast amounts of Russian oil at a discounted price. Last June, Russian supply volumes were 30 times higher than in 2021, which brought Russia’s share to 20% of India’s total imports.

Risk of renewed pressure on Indian fundamentals

High commodity prices and global monetary tightening, especially in advanced economies, are putting pressure on India’s fundamentals. Indeed, the rising current account deficit and capital outflows – particularly portfolio investments – have been affecting India’s external liquidity. Soaring imports and the gradual decline in foreign exchange reserves could reduce the country’s import cover from more than 11 months in FY2020 to potentially less than 7 months in FY2022. In the current economic context, India’s weak public finances are also unlikely to improve soon. While government revenues remain under pressure, a boost in public investment spending in infrastructure and the temptation to reverse the sharp drop in food, fertiliser and fuel subsidies in the FY2022 budget amid high prices could keep India’s general government fiscal deficit around 10% of GDP for some years, at least until the 2024 elections. By then, India’s high public debt is projected to remain stable at around 86% of GDP and as a result may suffer the threat of losing its investment grade status from credit rating agencies. This sword of Damocles partly explains the government’s continued commitment to a cautious fiscal stance, as confirmed by the current push for the privatisation of State enterprises and banks. On a positive side, the banking sector has seen some improvement thanks to corporate deleveraging and the cleaning-up of heavy non-performing loans, and in the second quarter of 2022, bank credit growth accelerated sharply to 14% in nominal terms – a three-year high – reflecting stronger demand and supply. However, interest rate increases and high inflation might affect this momentum.

Modi as the favourite for a third term in 2024

In these times of uncertainty, the political situation offers a clear view with PM Modi firmly in power and looking confident to win a third consecutive mandate in the 2024 general elections: the latest State elections have confirmed once again the persisting popularity of its BJP party across most of India. Yet in spite of the political stability and democratic elections, the domestic situation remains far from calm and is not a source of optimism. First, communal tensions have sharply increased since PM Modi came to power and present a higher threat to future domestic stability in the country. Second, social protests have been on the rise for some time due to high and rising living costs, high unemployment (above 8% last month) since the pandemic and the unpopular large privatisation process while formal jobs are scarce. In addition, the recent resumption of large-scale protests from farmers due to unresolved issues promise to present another hindrance to PM Modi’s rule.

A stable outlook

Country risk ratings present a stable outlook for both short-term political risk (2/7) and business environmental risk (a rather high E/G). The negative prospects for inflation, the Indian rupee and supply chain disruptions make the overall outlook challenging for the latter. As for the MLT political risk (3/7), poor public finances, heavy fuel imports weighing on the current account deficit and communal tensions are the dominant downside risks that will need to be closely monitored. Furthermore, this summer’s record mass floods in neighbouring Pakistan highlight how vulnerable India’s outlook also is to climate change via prolonged droughts, erratic monsoons and melting Himalayan glaciers.

Analyst: Raphaël Cecchi – r.cecchi@credendo.com