Brazil: Largest Latin American economy displays remarkable resilience amid headwinds

Highlights

- Home to large metal mineral reserves and one of the world’s food baskets, Brazil has major commodity opportunities in the offing.

- A high dependency on commodities has led to a deindustrialisation process, deforestation concerns and vulnerability to a commodity downturn.

- The central bank successfully won the battle against double-digit inflation, but further challenges may lie ahead as inflation is expected to remain sticky.

- The country’s Achilles heel is public finances, especially in the light of rising climate change-induced natural disasters.

- The MLT political rating – upgraded in 2022 – and short-term political rating have a stable outlook.

Pros

Cons

Head of State and Government

Population

GDP per capita

Income group

Main export products

Largest Latin American economy displays resilience amid headwinds

In recent years, the world’s ninth largest economy has performed strongly. The economy bounced back faster to its pre-pandemic path than its regional peers following the Covid-19 crisis, while also surpassing its own historical performance. Real GDP growth averaged around 3.6% between 2021 and 2023, more than double the decade-long average of 1.4% between 2010 and 2020 (see graph below). That being said, an environment of relatively high interest rates and lower levels of economic growth in China, its most important trading partner, is weighing on the economy. In addition, various climate change-induced natural disasters have hit Brazil this year, such as devastating floods in Rio Grande do Sul in April/May and the most intense and long-lasting drought since records began in 1950, which has affected almost 60% of the country since July. The economic effects of the droughts are still unclear: the agricultural sector and hydroelectricity are key to the economy, but currently there is sufficient water for producing hydroelectricity and it is still quite early in the planting season. Nevertheless, real GDP growth is forecast at a remarkably resilient 3% for 2024.

The green transition and AI development could boost the economy

Economic growth is expected to fall to around 2.3% in the medium term, hampered by elevated interest rates and structural challenges such as subpar infrastructure, bureaucratic red tape, inadequate access to credit for companies and high trade barriers. Nevertheless, the long-awaited tax simplification reform (three decades in the making), which was approved at the end of 2023 and consolidates several taxes into a dual value-added tax (VAT) system, is expected to support economic growth in the medium term, depending on the exemptions granted. Downside risks to the forecast include Brazil’s vulnerability to climate-induced natural disasters, which have tripled since 1990, severe unrest as a result of a polarised society and a significant deterioration of public finances. On the upside, higher commodity prices and further development of critical minerals could boost economic growth – Brazil holds the third-largest reserves of rare earth elements (about 10% of the global total) but is only the sixth largest producer. Furthermore, the AI revolution also has great potential but is currently being held back by limited investments, limited data and a lack of framework. Finally, a world that is increasingly pulled towards geopolitical blocks could both boost and harm the economy. Brazil’s neutral stance might see more trade being redirected to its advantage, as happened in 2018 when China redirected its soybean imports from the USA to Brazil, but rising protectionism and tariffs, higher geopolitical uncertainties and volatility could have an impact on Brazil too, even when the country is not in the immediate crossfire.

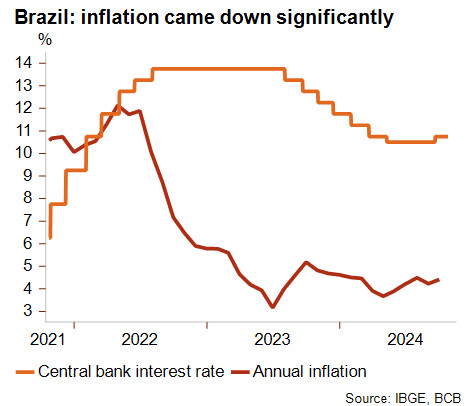

A successful decrease in double-digit inflation, but battle is not over for Brazil

In the wake of the Covid-19 economic impact, the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) successfully fought double-digit inflation. Alongside most Latin American countries, the central bank raised interest rates quickly and aggressively, one year ahead of advanced economies. As a result, inflation had already peaked at 12% by May 2022 (its highest level since 2003) and dropped back down to 3% by June 2023, meeting the BCB target rate and leading to aggressive interest rate cuts. However, the battle against inflation is clearly not over: amid a volatile exchange rate and rising inflation, the interest rate was increased again in September 2024 (see graph below). Further monetary policy tightening in the future is possible, as inflation is likely to remain a concern given ongoing geopolitical events, rising currency volatility and the potential impact of the severe drought.

Major commodity opportunities in the offing, but deindustrialisation comes with its risks

Brazil has major commodity opportunities in the offing. The country has become one of the world’s food baskets in the past two decades, and is the leading exporter of soybeans, sugar, beef, poultry, coffee and corn. It is also a key world player in ores and metals, and the world’s second largest exporter of iron ore. Moreover, the country is also likely to become a powerhouse for the green energy transition, because besides exporting rare earth minerals, the country is the fifth-largest lithium and copper producer in the world. Lastly, since 2018, it has been a net fuel exporter and the second-biggest oil exporter in Latin America, after Mexico.

On the downside, a worrying deindustrialisation process is ongoing. Between 1990 and 2007, manufacturing exports accounted for about 45% of current account revenues, but since then have gradually declined to almost a fifth of current account revenues in 2023. As a result, manufacturing imports are steadily on the rise, especially from China, which exports its manufacturing overcapacity in a broad range of sectors. This harmed the competitiveness of the Brazilian manufacturing sector, while the higher import tariffs imposed as a reaction could decrease its competitiveness further in the medium term.

Diversification will be one of the main challenges, as Brazil’s dependency on commodities (though this represents a broad category) makes it vulnerable to a commodity downturn, as seen in the second half of 2014 and in 2008. Furthermore, environmental concerns such as the deforestation of the Amazon for agriculture lands or oil and mining exploration have raised national and international concerns. As a result, the EU is planning to implement a deforestation law (as of 2025) that could affect about one third of Brazilian exports to the EU, while the USA has announced the launch of the Amazon Region Initiative Against Illicit Finance to combat nature crimes.

The country’s Achilles heel is its public finances, especially with natural disasters on the rise

Public finances are still Brazil’s Achilles heel. Important reforms were implemented in 2016 and 2019 to keep public finances on a sustainable path, but public debt – at 85% of GDP at year-end 2023 – remains substantially higher than the average for emerging markets. Moreover, Congress approved a new, more flexible fiscal framework that allows real spending to rise to 70% of annual fiscal revenue growth, if a primary fiscal surplus is not attained by 2025, this figure will fall to 50% of revenue growth (which is more flexible than the spending cap introduced in 2016). Public debt is therefore expected to rise to almost 100% of GDP by 2029 – a very high level. A further weakening of fiscal targets, as happened in April amid devastating floods, could deteriorate these numbers even further. Although the recently approved tax simplification reform could boost economic growth (and public revenues) in the long term, further reforms will be necessary to keep the public debt on a sustainable path, especially in the light of rising climate change-induced natural disasters. That being said, there are major mitigating factors. Despite high public debt, public interest payments remain at manageable levels for the country. Furthermore, the overwhelmingly domestic investor base (almost 90% of debt lies in domestic hands), the high share denominated in Brazilian reals (about 94% of debt), the large volume of liquid assets and substantial central bank holdings of treasury debt all help to mitigate risks.

Political risk ratings are stable

The MLT political risk rating, upgraded in 2022, has a stable outlook. The country has relatively modest current account deficits, which are mainly being financed by FDI, and moderate external debt ratios. However, weakening institutional indicators and public finances are a point of concern. The short-term political risk rating is in category 2/7 and also has a stable outlook, thanks to a large and relatively stable buffer of foreign exchange reserves and manageable short-term external debt levels.

Analyst: Jolyn Debuysscher - J.Debuysscher@credendo.com