Kazakhstan: More sustainable external debt in a challenging environment

- Orderly presidential transition in a context of rising social discontent.

- Main domestic vulnerabilities are the fragile banking sector and rising social tensions.

- Main external threats are a drop in commodity prices, trade tensions and lower EU/China growth.

- Downgrade of ST political risk rating to 3/7 due to the drop in foreign exchange reserves.

- MLT political risk rating upgraded to 5/7 in December 2019 amid lower financial risk.

Orderly presidential transition… with still a large role for the incumbent

President Nursultan Nazarbayev, in power since Kazakhstan’s independence in 1991, stepped down in March 2019. As a result, a presidential election was organised in June. It was won with 70.8% of the vote – a rather low score according to Kazakh standards – by Mr Tokayev, the candidate supported by Nazarbayev. The presidential transition happens in a period of growing social discontent driven by lacklustre socioeconomic developments. In the near term, the authorities are likely to focus on measures aimed at promoting growth, improving living standards and maintaining social stability, which should weigh on public finances.

Recently, deadly clashes between two different ethnic groups erupted in a village close to the border with Kyrgyzstan. Such event exposes the fragility of inter-ethnic relations in Kazakhstan where a complex mix of ethnicities largely lived in harmony so far.

In October 2019, President Tokayev handed over significant executive powers (such as the power to veto the president’s cabinet’s choices except for defence, foreign and interior ministers) to his predecessor. The latter has retained significant power with the chairmanship of the Security Council and of the ruling Nur Otan party and his membership in the Constitutional Council. Moreover, his daughter Dariga Nazarbayeva became the Speaker of the Senate indicating that the dynastic succession scenario remains probable. Looking forward, given the presence of powerful elites and clans who have amassed a lot of wealth, they are likely to negotiate among themselves with the aim to maintain political stability.

Kazakhstan, a close ally of Russia and member of the Eurasian Economic Union, tries to maintain a good relationship with Russia, the West and China. China is an important trade and investment partner of Kazakhstan. As a result, the Kazakh economy is not immune to the indirect impact of trade tensions between the US and China (even if tensions are easing in the short term). Moreover, discontent and protest are fuelled by fear of Chinese expansion. Last but not least, since the death of the Uzbek President Karimov (2016), the relationship between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan – two traditional rivals for regional leadership – has strongly improved which led to more trade between the two neighbours.

Strong growth and high reliance on commodities

After a deceleration in 2015-2016, real GDP growth rebounded. Amid large domestic demand partly boosted by higher social spending, GDP growth was robust last year (at about 3.5%) despite a slowdown in oil production driven by the planned shutdowns in its three leading oil fields: Tengiz, Kashagan and Karachaganak. In 2020, growth is expected to reach around 3.5-4% on the back of a recovering oil production. The main risks to the outlook arise from a sharp drop in commodity prices (oil and metal) and lower growth in the EU, China and Russia, its main trade partners. Of course, the fallouts from the coronavirus may negatively impact Kazakhstan’s economy (through lower oil prices, and slower growth in China). The importance of these impacts depends on the length of the outbreak, which so far is unknown.

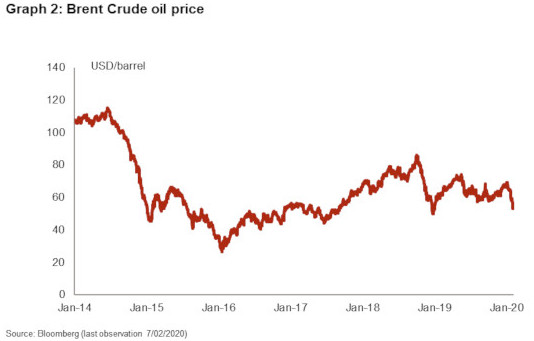

Following the sharp drop in oil prices that started mid-2014 (cf. graph 2), the current account balance turned into a deficit in 2015 (cf. graph 3). Compared to 2018, the current account deficit increased in 2019 amid a less favourable external environment and lower oil production. Despite the more difficult external environment, the exchange rate remained broadly stable in 2019.

Since 2016, foreign direct investments (FDI) (mainly in the oil and mining sector) have been sustained, boosted by the development in the Tengiz oilfield expansion (which is expected to be completed in 2022-2023). Looking ahead, the capacity to attract more FDI – in a country where the state continues to play a large role in the economy – will depend on the global financial environment and the authorities’ capacity to move forward with their ambitious privatisation programme (cf. plans to sell stakes in the oil and gas company KazMunayGas, uranium company Kazatomprom, railway company Kazakhstan Temir Zholy and mining firm Tau-Ken Samruk). In November 2018, 15% of the shares of Kazatomprom were sold in London and on the new Astana International Exchange. Since then, no other large privatisation took place whereas small state-owned enterprises were sold.

Still sound public finances despite deterioration

The central government finances are sound but there is still a large opacity in public-sector figures. After having surged from 15% of GDP in 2014 to 22% in 2015 (still a low level), general government debt has remained broadly stable. In 2019, the overall fiscal balance is likely to be slightly in deficit as social transfers in education, health and housing and debt relief for low-income earners increased more rapidly than revenues. Thanks to its solid general government balance sheet, the authorities issued a 15-year Eurobond at a relatively low rate in September 2019.

That being said, public-finance vulnerabilities arise from reliance on oil revenues, rising social tensions (and thus the temptation to spend more to stem social unrest), and contingent liabilities from the PPP, the state-owned enterprises and the banking sector that remains fragile. Indeed, the fall in oil prices and the deprecation of the tenge in 2014-2015 hit the banking sector hard. Thanks to the authorities’ support in the form of liquidity, subordinated loans, and purchases of bad assets, the banking sector recovered. However, the level of non-performing loans remains relatively high and the preliminary results of the ongoing asset quality review show that an additional capital of USD 1.2 bn might be needed. The asset quality review provides an opportunity to fix the banking issues.

While loans to corporates have remained limited and expensive (on average above 12% for loans to legal entities in local currency in November 2019), loans to households have increased leading to rising vulnerability in the banks. The lack of access to credit and relatively high financing cost are also factors that constrain Credendo’s commercial risk, which is currently classified in category B (on a scale from A to C).

Lower financial risk

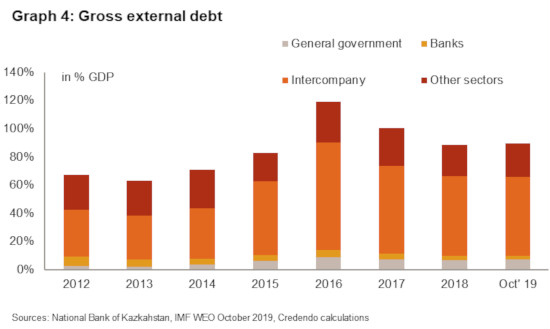

The relatively high financial risk – the main driver of Kazakhstan’s MLT political risk – has drastically decreased compared to its peak reached in 2016 on the back of fallen external debt and debt service ratios. As a result, Credendo decided to upgrade its MLT political risk classification from category 6/7 to 5/7 in December 2019.

The external debt dynamic is and remains sensitive to exchange-rate fluctuation. As highlighted in graph 4, a large share of external debt consists of intercompany loans (more than 60% in October 2019), which is a factor that somewhat mitigates the financial risk. It sharply increased in 2015 and 2016 (in absolute and relative terms) and has decreased in relative terms since then. The general government’s external indebtedness – although it slightly increased – is very limited. The external debt of the banking sector is also very limited and has been on a decreasing path amid the banking sector consolidation. The debt of the other sectors is largely stable. Last but not least, Kazakhstan possesses external assets (National Fund for the Republic of Kazakhstan - NFRK) worth 35% of GDP in 2018, which is another risk-mitigating factor.

Gross foreign exchange reserves under pressure

The gross foreign exchange reserves (excluding gold) have been under pressure over the past years. On top of that, they dropped sharply last year (cf. graph 5) as government and state-owned enterprises repaid external debt, and the central bank intervened to support the currency – even if it had decided to leave the tenge free-floating in August 2015 rather than to defend a trading band to the USD and to adopt an inflation-targeting framework – following portfolio outflows. As a result, the foreign exchange reserves of USD 10.2 bn covered less than 2 months of imports in November 2019 (their lowest relative level since 2000). This sharp drop led Credendo to downgrade its short-term political risk rating – which represents the liquidity of a country – to category 3/7 in 2019.

Analyst: Pascaline della Faille – (P.dellaFaille@credendo.com)