India: Modi’s likely third mandate to run country on a fast-growth trajectory

Highlights

- PM Modi is expected to win a third mandate following the ongoing elections.

- Hindu nationalism, increasing economic self-reliance and India’s global standing will remain priorities for the next government.

- The strong real GDP growth outlook is clouded by the job crisis and wide inequalities.

- India has strong macroeconomic fundamentals, but weak public finances and climate change vulnerability are risks that call for caution.

- In the near term, country risk ratings will remain stable.

Pros

Cons

Head of State

Head of Government

Population

GDP per capita

Income group

Main export products

PM Modi’s success story to continue with policy continuity ahead

The success story of 73-year-old PM Modi is likely to open a new five-year chapter. Such an achievement would bring his length of service only second to Jawaharlal Nehru (16.5 years) in independent India’s history, with the incumbent PM and his BJP party once again the clear favourites to win the general elections to be held between 19 April and 1 June. His charisma and strong leadership, Hindu nationalism and the rise of India’s global standing in particular, as well as a solid economic track record, generous welfare transfers and business-oriented government policy, are some of the many reasons that explain Modi’s enduring popularity. At the same time, the fragmented opposition – despite the belatedly formed but and substantial INDIA (Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance) coalition that has emerged pre-election – and the lack of a strong rival leader (notably from the historic Indian National Congress) in the face of the strong BJP political machine, not to mention legal barriers for the opposition such as the recent arrest of Modi’s main opponent Arvind Kejriwal – Delhi’s chief minister and leader of the AAP party – , have facilitated Modi’s political destiny. As a result, the BJP’s number of seats in Parliament may rise even further after the current elections.

A new PM mandate for Modi would allow policy continuity, by maintaining particular focus on Hindu identity, foreign policy and the economy. Reduced political freedoms, brought to light by US-based non-governmental organisation Freedom House, and Modi’s Hindutva agenda have most likely been the most controversial aspects of his domestic rule, including the recently implemented “Citizenship Amendment Act” passed in Indian Parliament. According to the latest Democracy Index published by the Economist, these factors have fuelled perceived democratic erosion in relation to the high levels of 2014 and contributed to intensified communal tensions and religious violence, especially against the large Muslim minority. Therefore, further steps in that direction would be a rising source of internal instability risks.

Active foreign diplomacy to raise India’s international standing

Modi is expected to pursue the active and successful foreign policy witnessed during his second term. On the world stage, this consists of a pragmatic and strategic approach that raises India’s international profile among Western, emerging and developing countries in the context of a shifting geopolitical order. On the one hand, Modi will strive to keep friendly ties with the West as opposed to China, play an active role in the Indo-Pacific and negotiate bilateral trade deals. On the other hand, he will ensure that India is seen as the leader of the Global South as opposed to Beijing, by defending their case in talks on climate change financing through its participation in non-Western institutions (such as BRICS), among others, and increasing non-USD trade, including with sanctioned countries such as Russia, as long as Indian interests benefit and do not breach US or EU sanctions. Meanwhile, in the face of China’s rising regional presence, Modi will ensure that the strengthening of India’s sphere of influence on the Indian subcontinent remains a foreign priority.

A performing economy clouded by a job crisis

The economy should remain another clear dividend of Modi’s rule, and large-scale infrastructure development has been a major trademark during his first two mandates. In recent years, his government has committed to ambitious goals towards economic self-reliance by boosting manufacturing sectors such as defence, automotive, EVs and semiconductors, while the energy transition away from the still very dominant coal and further digitalisation are also expected to remain investment priorities in the coming years. Job creation will remain another government priority, but has been disappointing to date.

Indeed, while India has become the world’s most populous country, in practice national demographics fail to bring benefits given the lack of available and good quality jobs, as well as the low labour participation of women. Consequently, official unemployment is high at around 8-9%, but a dominant share of total employment in the country remains informal. The main concern lies in the youth category, where more than 40% could be jobless. Besides the job crisis and despite a reported decline in extreme poverty to 12% of the population (source: World Bank), India is still a nation with widespread poverty and wide inequalities. The strong economic performances of this century have primarily benefited the middle class, with the upper class gaining disproportionally from wealth creation. It is worth noting that India still has a GNP per capita (USD 2,390) well below other founding BRICS countries and large Asian countries, except Pakistan. Improving this trajectory will therefore be of great importance for Modi’s political legacy.

A positive outlook for the world’s fastest-growing large economy

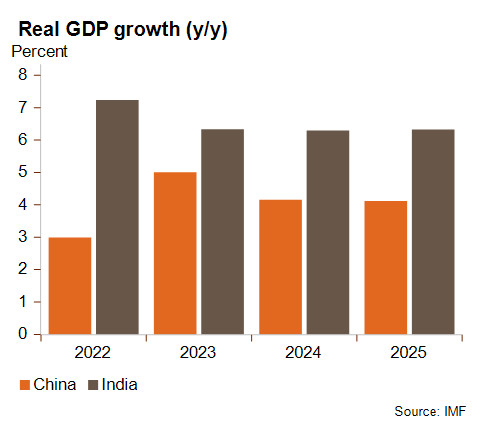

GDP growth is expected to reach 6.8% in FY 2024 (April 2024 to March 2025). The IMF recently forecast a slightly lower but still strong rate of 6.5% in the medium to long term (below graph is based on data from IMF WEO October 2023).

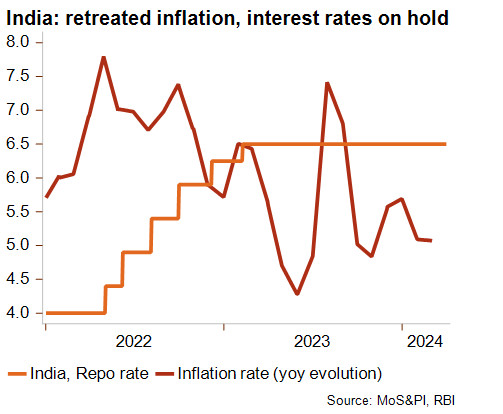

The strong economic momentum is driven by robust domestic demand and aided by solid economic prospects and a gradual decline in inflationary pressure (+5.1% in February, within the Reserve Bank of India’s target inflation band since September 2023). The Reserve Bank of India nevertheless continues to keep its policy rate at 6.5%, in particular given the persistently high inflation on food prices.

Furthermore, strong investments in infrastructure, especially transport and digital, a dynamic manufacturing sector on the back of self-reliance goals and an improved banking sector health are contributing to the positive economic picture, which is also reflected by the current stock market boom.

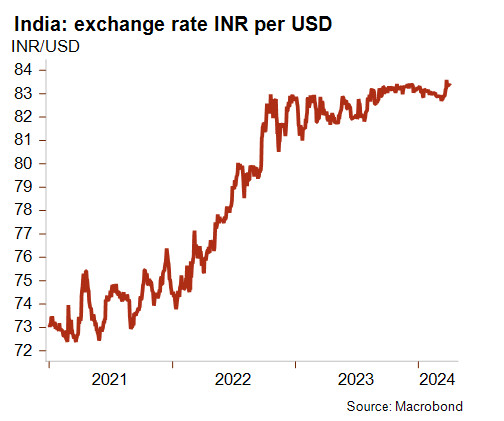

India’s balance of payments has also been evolving favourably. As for its regional neighbours, the war in Ukraine had a sharp negative impact on the trade balance through much higher energy and food import costs, despite soaring imports of cheap Russian oil, which has developed from a modest initial contribution to become the country’s main oil supplier. The Indian economy remains largely dependent on imported fuel (more than 35% of total imports) and thus vulnerable to high prices, but the country has been enjoying a surge of foreign direct investments (FDI) and portfolio inflows since 2023 and these volumes are expected to remain high and on an upward trend given India’s positive long-term prospects. Regarding FDI, India is seen as an attractive and safer destination for multinationals in their de-risking strategies away from China, amid sharp US-China rivalry and deteriorating European ties with China. To obtain a lasting boost in FDI in the manufacturing sector, more free trade agreements could become necessary as India suffers from its non-participation in regional trade agreements and limited bilateral deals. Large investment inflows allow for easy financing of the current account deficit, which has fluctuated at around 2% of GDP since 2022 and is forecast to stay around this level in the coming years. The Indian rupee has therefore been supported and has roughly stabilised against the US dollar, albeit at a historically low value, since November 2022.

Persistently weak public finances

Public finances remain a chronic weakness of India’s macroeconomic fundamentals. The Covid-19 pandemic further deteriorated these funds after the huge government fiscal stimulus (estimated at 10% of GDP) brought the public debt to 88% of GDP in FY 2020 and fiscal deficit into double-digit figures. Since then, the situation has improved somewhat, with public debt expected at 82% of GDP in FY 2023.

However, wide fiscal deficits in the range of 7-8% are still expected in the coming years, meaning that the decline in public debt – to 80% in the medium to long term – will be very slow, and will keep India in a delicate fiscal situation with heavy interest charges close to 30% of total public revenues (the highest levels since FY 2005). Therefore, the government must stay committed to fiscal consolidation to prevent any worsening of the situation and to maintain its investment grades from credit rating agencies. This will include a spending restraint, on high subsidies for food and fertilisers for example, and potential privatisations, notably in the banking and insurance sectors. However, given that divestment plans in previous years were very far from government targets, bold privatisation plans look somewhat uncertain.

High socioeconomic exposure to climate change

The year 2023 again showed how vulnerable India is to climate change impacts, particularly through more extreme weather events such as heatwaves and droughts followed by more erratic and intense monsoon rainfalls. These natural disasters will intensify with the acceleration in climate change, posing a particularly grave risk for 45% of the labour force still active in agriculture and clouding the country’s long-term economic potential. As a result, just like a rising number of other countries, India can expect to face decreased harvests of basic foods. Since July 2023, much weaker rice harvests have led the Indian authorities to impose a mix of bans and restrictions on rice exports, putting global supplies under stress and leading to sharp price increases. Trade restrictions related to food security concerns are likely to become more frequent in the future, as countries increasingly suffer the effects of climate change.

A stable to positive outlook for country risk ratings

The business environment risk has gradually improved over time, leaving the pandemic peak behind (G/G at the end of 2020) and more recently translating into an upgrade to C/G within a favourable economic context. As for the political risk ratings, the outlook is stable for the short-term (2/7), supported by comfortable liquidity, and the medium-to-long-term (3/7), amid low external debt.

Analyst: Raphaël Cecchi – r.cecchi@credendo.com