Gas: Energy crisis will weigh on industrial production in Europe and Asia

A rapid shift from over- to undersupply

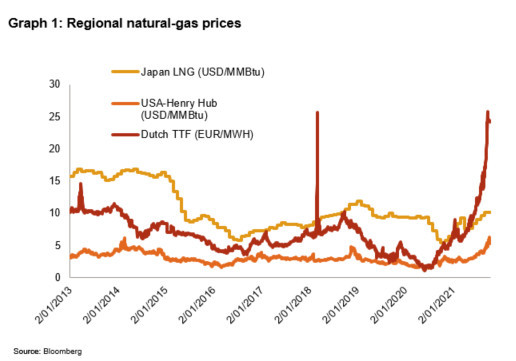

All over the world, gas prices have shown a rapid surge in the last few months. In some regions, they even reached record high levels. In Europe in particular, prices are more than 5 times higher than their pre-crisis level (cf. graph 1). Starting from a surplus position before the Covid-19 outbreak, the LNG market has experienced a strong tightening due to demand growth exceeding supply growth. Indeed, the economic recovery following the Covid-19 crisis, is pushing global demand – in China in a first stage. This is associated with a multitude of other global or regional, temporary or more structural factors that explain this boom.

Natural-gas price increase implies production cuts for European factories

Europe is increasingly dependent on LNG in its energy mix, as the internal supply of pipeline gas (from Norway and the Netherlands mainly) is in progressive decline, while imports from the principal pipeline gas supplier, Russia, were roughly constant in the few pre-Covid years and consumption was fairly stable. Nevertheless, Europe still plays the role of global gas balancing market, soaking up LNG supplies that are left after the needs of other regions in the world have been met. With mounting demand from Asia and Latin America (where Brazil’s hydropower production was badly hit by the drought), less LNG was available for Europe. Additionally, European gas production (in the EU and UK) declined by 24% in the first eight months of 2021, compared to the same period in 2019, and pipeline gas from Russia was reported to be 16% lower in the same period. While supply has considerably fallen, demand has surged because of the activity resuming, low gas stock availability after a prolonged winter that lasted until May implying large restocking needs, and feeble wind power generation this summer. This imbalance between demand and supply growth has contributed to the dramatic surge of gas prices in Europe. While this is good news for the upstream gas segment (i.e. exploration and extraction) which is making exceptional profits, gas suppliers and distributors are being heavily impacted. Retail electricity companies are facing large headwinds as well, as they are affected by the rising wholesale gas prices. In addition, some companies are unable to pass those costs on to consumers, due to new regulations to protect consumers that have been implemented in some countries.

In fact, high gas prices have repercussions across many other sectors. Most importantly sectors that use gas not only as an energy source, but also as a feedstock. This is the case for the fertiliser industry, which uses gas for the production of ammonia entering in the composition of fertilisers. With the production cost increasing dramatically, several fertiliser facilities have had to reduce or cut production. This was the case for two of the UK’s big industrial fertiliser plants, which had to shut down this month, but finally received financial support from the UK authorities – at least temporarily. Yara, the Norwegian phytochemical group, announced that it would reduce its European production of ammonia by 40%, and Austrian chemicals group Borealis also reduced it. Lower fertiliser production itself implies lower CO2 production, as the latter is a by-product of ammonia and enters the supply chain of many products. For example, as CO2 is used to stun cattle before slaughter, meat facilities are affected. Soda factories should also be impacted. And supermarkets have not been able to have ice cream delivered as the supply of dry ice that is used for transporting ice cream has been cut.

The energy crisis is also unfolding in Asia

In Asia, natural-gas prices are also rising as demand is strong in a context of robust activity, and coal prices are high amid a coal supply shortage in China and India, implying a switch towards gas. In China, combined with emission restrictions, this resulted in electricity shortages, affecting north-eastern Chinese provinces in particular. Consequently, factories in sectors such as aluminium, electronic components or automobiles, have been ordered to use less power or even to close for a few days.

No relief in sight

The ongoing energy crisis could weigh significantly on this winter’s industrial production. Indeed, gas prices are expected to stay high over the next few months, as winter is approaching in the northern hemisphere. We already observe a massive switch to oil products for power generation, which contributes to the increasing oil prices. However, even a complete switch to oil liquids – while potentially displacing about 15-20% of the typical spot LNG trade in a winter month – would probably be insufficient to bring prices back to low levels. As for the European supply, relief due to more deliveries from Russia is uncertain. Even if Nord Stream 2 becomes operational before the end of the year, Russian production is already at a record high and exports are constrained by indigenous needs in a tight domestic market. Unless we see a significant slowdown in the Chinese economy – allowing more LNG to be shipped to the rest of the world – or a (very) mild northern-hemisphere winter, industries will have to cope with the rising energy costs, to the detriment of their profitability.

Analyst: Florence Thiéry – f.thiery@credendo.com