Iraq: Recovering from years of conflict, but political risks expected to remain high for years to come

- Political violence is the main driver of the MLT risk but this is expected to remain stable for years to come.

- US-Iranian tensions and insurgency attacks pose the largest risk for Iraq.

- Renewed sectarian tensions are unlikely to build up in the medium term.

- Debt relief in the mid-2000s has put debt levels on a sustainable path.

- An oil price drop could lead to a rapid deterioration of economic indicators, although they would remain sustainable in a negative scenario.

Since the removal of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraq has gone through a turbulent period of civil war marked with sectarian tensions and recurring flare-ups of political violence. Throughout the years, this has significantly impacted the institutional framework of Iraq. Given the relatively low external debt levels, and also taking into account the significant reliance on oil revenue, the main driver of the MLT political risk has been the challenging political situation ever since the country received debt relief in 2005. However, the security situation has been improving steadily since IS was defeated in mid-2017, although risks related to the very fragile political situation remain. As explained in this article, Iraq is currently facing five key challenges that are driving the MLT political risk: (i) the risk that tensions between the Kurdish government and the federal government could resurface in the medium term; (ii) the ongoing risk of popular protests, especially during the summer months, although this will not destabilise the country; (iii) the possible further increase of geopolitical tensions between Saudi Arabia and the USA on the one side and Iran on the other, which could have spillover effects in Iraq; (iv) the Sunni and Shi’a communities remaining divided; and (v) the small but not impossible risk of insurgency attacks and the uncertain future role of the Popular Mobilisation Units. A combination of the third and fifth elements listed above would be the strongest driver of the medium-term political risk in Iraq. However, while it is prudent to acknowledge these weaknesses, at present none of these elements is expected to lead to a sudden, significant or large deterioration of the political risk situation in Iraq in the medium term. Therefore, Credendo has decided to upgrade Iraq’s MLT political risk classification to category 6 (from 7).

Political violence as a key driver of country risk

Since the removal of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraq has gone through a turbulent period of civil war marked by sectarian tensions and recurring flare-ups of political violence. These started immediately after the removal of Saddam Hussein, when the USA installed a provisional authority, as it was not able to handle the tasks at hand. As early as 2004, a Baathist insurgency started to attack symbols of the new state and over time developed into a full-blown insurgency against the new government. As this happened, people became divided over sectarian lines and both Shi’a and Sunni insurgency groups developed across the country throughout 2004.

Then in 2005, a Transitional Government (TG) was formed. It was dominated by Shias and Kurds because the Sunnis had boycotted the election. The TG was tasked with handling the rising number of insurgency attacks and with drafting a new constitution for Iraq, which outlined a parliamentary system in which the executive power was vested in the Prime Minister and the council of ministers. Given their absence from the TG, the new constitution hardly met the demands of the Sunni population but it did satisfy most aspirations of Shi’a and Kurdish leaders. This was already a clear source of frustration for the Sunnis following the December 2005 elections, which were organised after the new constitution came into effect and saw Nouri al-Maliki become Prime Minister. As a Shi’a, he headed the Islamic Dawa Party. Al-Maliki remained Prime Minister until 2014 and soon became one of the most powerful political leaders in Iraq.

In the course of 2006, the country started to slip into an all-out civil war when Sunni insurgents destroyed the golden dome of the al-Askari mosque in Samarra. This shrine is one of the holiest places of the Shi’a community and consequently the bombing led to a chain of reprisal attacks against Sunni mosques throughout the country. In 2007 and throughout 2008, violence in Iraq started to decline once more. An element that played an important role here was that the USA started to use Sunni Arab militias in order to stamp out insurgents in their own communities, which helped the Iraqi government to reassert control over many Sunni towns and villages. Yet, while the security situation improved, the political situation remained gridlocked in discussions concerning the interpretation of different elements of the constitution and the role of the government. It showed that Iraq was deeply divided across sectarian lines.

From 2008 to 2009, al-Maliki was able to expand his influence over Iraqi politics. He launched multiple anti-insurgency attacks throughout the country that served both as an attack against the active insurgent groups but also as a way to eliminate opposing militias. He further alienated the Sunni population, as some Sunni militias were the prime target. Al-Maliki was able to stay Prime Minister until 2014 thanks to his strategic use of patronage, his control over the coercive instruments of the state and his network of allies throughout the south of the country, but most importantly due to the weakness and incoherence of the opposition. Over time, he expanded his influence over all independent institutions such as the central bank and the election commission.

In August 2010 President Obama announced an end to all combat operations in Iraq. The security situation had improved and this was a way of defusing the domestic opposition to the Iraq War. By the end of December 2011, all US military units had departed from Iraq. However, around the same time that Obama announced an end to the main combat operations, summer protests started in Iraq in the form of popular demonstrations across the country among both the Sunni and Shi’a populations. The protests centred on the lack of basic services such as electricity and targeted the endemic corruption. Since 2010, these protests have reoccurred most summers but 2010 and 2011 were certainly the peak. By mid-2012, the protests had taken a more dangerous turn as they ¬were centred mainly in the Sunni parts of the country. Moreover, renewed insurgency attacks then started, paving the way for the rise of Islamic State in 2014.

Haider al-Abadi became Prime Minister after the 2014 elections, taking over from al-Maliki even though his party had come out first in the election. The removal occurred when al-Maliki did not secure a majority and after both the USA and Iran had asked him not to cling onto power, and this removal should be regarded as a positive development because al-Maliki had alienated the Sunni community. Al-Abadi’s immediate task was dealing with IS, which by mid-2014 had succeeded in capturing significant parts of Iraqi and Syrian territory and declared a caliphate in the city of Mosul. This proved a challenge since the Iraqi army had disintegrated and al-Abadi thus needed to rely on Shi’a militias (which over time would transform into the present day Popular Mobilisation Units, PMU) and the Kurdish Peshmerga forces to stem the advance of IS.

IS was able to rise in importance as it clearly enjoyed support in the Sunni communities, which were marginalised under al-Maliki’s leadership. Al-Abadi tried to reverse this marginalisation with promises to address some of the key demands of the Sunni community. Nevertheless, this turned out to be difficult to implement given the opposition he faced from the Shi’a and Kurdish groups. Over time, with the support of the PMU, Kurdish Peshmerga forces, international and Iranian forces, Iraq was able to defeat IS in mid-2017.

After the defeat of IS, Iraq faced strong challenges as the country looked to cope with the consequences of years of conflict. This had left an estimated 3 million people displaced internally, 30% of the population in need of humanitarian assistance, and infrastructures such as those related to electricity production and water distribution heavily destroyed. Meanwhile, the defeat of IS triggered another ethnical conflict, namely the Kurdish bid for independence, and in September 2017 the Kurdish political parties organised a referendum on their independence. This was arranged in all the territories controlled by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), despite strong opposition from the federal government and from Turkey and Iran, who worried that the referendum could encourage the Kurdish populations in their territories to push for independence. Unsurprisingly, the outcome of the contested referendum showed that 93% of voters were in favour of independence.

The federal government responded swiftly to the referendum and the subsequent bid for independence. International flights to the Kurdish region (KRI) were halted and the federal government retook control of the oil-rich territories of Kirkuk and Nineveh (two regions controlled by the Kurdish government but not officially part of the Kurdish region). Turkey threatened to close the oil pipeline exporting oil from the Kurdish region to Turkey, Kurdish banks were excluded from Iraq’s banking system and Turkey and Iran closed their borders with the KRI. Moreover, the referendum alienated a number of Kurdish allies, including Western partners. These measures had a strong impact on the Kurdish economy, especially the loss of the oil fields in Kirkuk and Nineveh, which meant that the Kurdish government lost around 50% of its revenue. As a result, the Kurdish referendum proved to be a major miscalculation, and the President of the Kurdish region, Masoud Barzani, who had been the main defender of the bid for independence, announced his resignation. Thereby the Kurdish government buried their bid for independence.

Federal parliamentary elections were organised in May 2018. They were more fragmented than before, as a number of the parties had split, but on the other hand it was reassuring to see that the main blocs attempted to appeal beyond a single ethnic group. This contrasted with the past approach of al-Maliki, who focused his campaign in the Shi’a part of the county and rallied the Shi’a electoral base by taking a hard line on the Kurds and alienating the Sunni population. The elections were won by the populist anti-establishment party Saairun and the Fatah Alliance, created by Hadi al-Ameri, a prominent former PMU commander, which came second. The formation of the new government took time but it was finally complete in October 2018 after al-Abadi had indicated that he would not hold onto power. Abdul Mahdi became Prime Minister and is considered a conciliatory figure that is accepted by both the USA and Iran. He formerly served as Minister of Finance and Minister of Oil in various governments after 2004.

Despite these improvements, numerous challenges remain. Currently there are five key elements driving the medium- to long-term political risk:

- First, tensions between the Kurdish government and the federal government could resurface in the medium term. However, the strong response of the federal government has buried the Kurdish bid for independence and the current Kurdish government is cooperating with the federal government. While it is expected that there will be recurring discussions over the share that the Kurdish region can receive from the federal budget, the Iraqi-Kurdish tensions are not expected to materialise into a full-blown crisis. It is also reassuring to see that the current Prime Minister, Abdul-Mahdi, has an effective track record for communicating with the Kurdish leadership.

- Second, popular protests – against the low quality of services, corruption and electricity and water shortages – have reoccurred on multiple occasions, especially during the summer. Last summer, in the oil-rich Basra province, protests were more severe than usual and led to the destruction of the governor’s office, the provincial council and the Iranian consulate. Nevertheless, these recurring protests are currently not considered a major risk to political stability. The Basra summer protests drew global attention and hurt then Prime Minister al-Abadi’s position but they did not lead to any political instability. Looking forward, the government has launched multiple large scale investment programmes, such as a USD 15bn deal with General Electric to upgrade the electricity network. These investments should therefore address some grievances and thus, over time, reduce the intensity and frequency of the protests. While it is not impossible that some protests could still take place this summer or in the future, they are not expected to lead to major political instability.

- Third, geographically, Iraq is squeezed between Saudi Arabia and Iran, two opposing regional powers. Historically, Iran has had a strong presence through its ideological influence with the Shi’a community, through its influence on the PMU forces and because Iraq still relies on Iran for part of its energy needs. This is a thorn in the side for the USA, at a time when the Trump administration has increased its pressure on Iran. Saudi Arabia and the USA are actively working to try to reduce Iran’s global influence, which could lead to increased geopolitical tensions. More specifically, for Iraq, the rise in geopolitical tension could result in political gridlock as there are multiple blocs in parliament that actively support Iran. More worrying would be if Iran were to use its control over the PMU to attack US assets in Iraq. While in the last two months there were a few small-scale rocket attacks on US assets in the country, a large scale attack by the pro-Iranian PMU on US assets in Iraq is still considered unlikely. There are multiple important voices in the Iraqi government and among the clerics, such as al-Sistani’s, calling for non-interference of foreign forces in Iraq. Additionally, Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi has issued a decree that further regulates the PMU, meaning that in theory they can no longer operate under their own name or be politically active. This entered into force in August 2019, although it will take much longer to enforce it. Nevertheless, it is a first step towards increasing the control over the PMU and thus reducing Iran’s military capability in Iraq.

- Fourth, Sunni and Shi’a communities remain divided and a flare-up of tensions could happen, although this is considered unlikely. Since the al-Maliki presidency and the rise of IS, Shi’a leaders have realised the importance of supporting the Sunni community and hearing their grievances. In the last elections, the broadening of the parties beyond their own sect was a clear indication of this.

- Finally, there is a risk of renewed insurgency attacks and the future role of the PMU is uncertain. This, in combination with US-Iranian tensions, is currently considered the main driver of the MLT political risk in Iraq. The question is whether the PMU will be willing to place their loyalty to the country over their loyalty to a specific individual or party. Nevertheless, given that the parties and individuals they currently report to are aiming for the stabilisation of Iraq, as highlighted during their fight against IS, it is not expected that the PMU will be a destabilising factor. On the plus side, the PMU, together with Kurdish forces and the Iraqi military, currently have strong control over the Iraqi territory, thus inhibiting any insurgent group from operating there.

Therefore, while the political risk is by far the strongest driver of risk in Iraq, we are currently seeing a steady stabilisation, despite the fact that years of conflict have significantly weakened the institutional framework in Iraq.

Economic vulnerabilities lie ahead

Iraq has enjoyed support from multiple IMF programmes. First of all, in 2004, an Emergency Post-Conflict Assistance agreement was concluded. In 2005, 2007 and 2010, three stand-by agreements (SBA) were concluded; the 2005 and 2007 SBA were purely precautionary while the funds of the 2010 SBA were disbursed. The 2010 programme went off-track when oil prices started to rise, providing the government with a significant revenue windfall that reduced the need for external funding. After the oil price boom, Iraq sought support from the IMF once again, as it was faced with falling oil revenue and with the cost of the war against IS. Funds were disbursed under the Rapid Financing instrument in 2015 and this was followed by an SBA in 2017. Performance under the last IMF programme (July 2016-July 2019) was again poor, as the programme went off-track as early as August 2017 and expired in July 2019.

One issue of the IMF programmes is that Iraq usually had a relatively strong balance of payment position, especially in the early years of IMF involvement and during the oil booms. This seemed to have provided the IMF with few carrots and sticks to motivate the Iraqi government to implement the required reforms, which is evident when looking at the evolution of government financials. Due to the ongoing conflict with IS and low oil prices, the public deficit reached 12.8% of GDP in 2015 and 13.9% of GDP in 2016. Once the oil price had recovered and the conflict with IS had come to an end, the public balance recovered to a 7.9% surplus by the end of 2018, which reduced the need for compliance with the IMF programme. Current IMF projections indicate that, as Iraq plans to launch multiple infrastructure programmes, it is expected to run a 4.1% deficit in 2019 and a deficit of around 5% in the medium term. However, because the public debt level currently stands at less than 50% of GDP and infrastructure projects are likely to support growth, the public debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to increase only slowly in the medium term. Nevertheless, the IMF has warned that large budget deficits could erode central bank reserves if they cannot be funded through external borrowing.

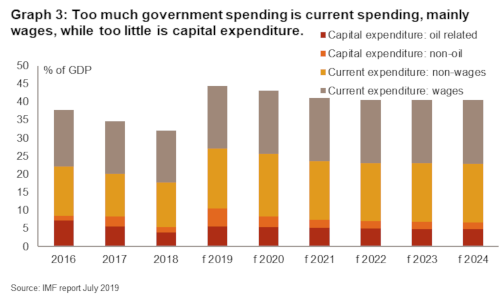

Concerning public finances, one of the main challenges for Iraq is the relatively high current expenditure, while the country needs higher capital expenditure in order to restore infrastructure. Public sector wages in particular swallow around 40% of public expenditure, up from around 25% in the years 2010-13. This partly reflects the patronage networks that are used by the various political parties, which will need to be brought under control if the country wants to continue investing in infrastructure. Another challenge is the strong reliance on oil and gas receipts, representing around 90% of total government receipts, while taxes represent only 5%.

A similar picture is also available when we look at the current account receipts. Hydrocarbon represented 92.4% of total foreign currency receipts in 2017, and the rise of oil prices over 2017 and 2018 thereby led to larger current account surpluses. In 2017 Iraq was running a current account surplus of 1.8% of GDP, while in 2018 it reached 6.9% GDP. Over the coming years, Iraq is expected to import more capital goods in the framework of large infrastructure projects and so the current account is expected to revert back into a deficit of -4.1% in 2019 and, in the subsequent years, it is expected to be around 3.5%.

Growth has been relatively volatile, reflecting the impact of years of conflict and fluctuating oil prices. Nevertheless, growth was 6.3% on average over the period 2005-16. In 2017 and 2018 it was subdued because of the oil production cuts and the remaining political uncertainty but, given the projected investments in the coming years, growth is expected to increase to 4.6% in 2019 and 5.3% in 2020. In the medium term, it is expected to be around 2.1%.

Debt forgiveness has improved the financial outlook

The financial situation of Iraq is strong because the country only has limited external debt given the large debt relief it received in the mid-2000s under the framework of the Paris Club. Total external debt stood at 69% of total export receipts or at 30% of GDP in 2018. While it is expected to rise in the medium term, as the government is likely to borrow externally in order to fund the infrastructure investment programme, the debt-to-exports ratio should remain below 80% in the medium term. Less than 15% of total external debt has a short-term maturity.

Given the relatively low external debt level, the external debt service is also relatively low. The country spent less than 3% of its current account receipts in 2018 on servicing its external debt, and on average only 3.7% in the last seven years, although this is expected to rise to around 9% of total current account receipts by 2022.

Iraq’s reserves are large and have remained stable in recent years. At the end of 2018, they were sufficient to cover around 9 months of imports and could even cover almost 90% of the total external debt. However, the IMF’s current baseline scenario projects a significant drop in reserves by 2024, given that their baseline scenario expects lower oil prices and limited borrowing capabilities to put pressure on reserves.

This highlights the biggest vulnerability of Iraq in terms of its economy, namely that the strong reliance on oil revenue in combination with the volatile oil price could deteriorate some of the economic indicators quite rapidly in the event that the oil price drops significantly. Yet debt levels are still expected to be sustainable even under the scenario of lower oil prices, indicating that the biggest risks remain political.

Analyst: Jan-Pieter Laleman – jp.laleman@credendo.com