Serbia: MLT political risk rating upgraded from 5/7 to 4/7

Serbia’s economy and government policies are on a virtuous path

Serbia continues to record strong economic and financial performance on the back of sound government policies while keeping its IMF programme on track, thereby allowing the political risk to continue to gain virtuous momentum. Since 2017, the last time that Credendo upgraded its MLT rating to category 5/7, Serbia’s fundamentals have continued to improve steadily. A solid domestic demand – including strong private consumption and booming construction – and foreign direct investment (FDI) rising to record levels have more than offset the impact from a slowing EU economy. GDP growth was therefore resilient at 3.5% in 2019 (from 4.3% in 2018), and is forecast to fluctuate at around 4% in the MLT. This projection could be revised downwards should the slowed EU economic momentum (including the impact from the coronavirus outbreak in China) become more pronounced and global protectionism rise further, and when taking into account Serbia’s export competitiveness problems. However, domestic demand has become a solid buffer against external shocks.

The current account deficit has increased slightly since 2017 but, from this year onwards, it is expected to be on a decreasing trajectory due to a possible FDI softening, which would curtail import growth. At the same time, it can rely on diversified sources of current account receipts. Meanwhile, this deficit is expected to remain fully funded by FDI, allowing the balance of payments to be safely in surplus for the next few years.

The path to EU membership continues to drive Serbia’s economic policies and development. The positive momentum in government policies is framed by the previous (2015-2017) and current IMF programmes, as the ongoing ‘policy coordination instrument’ remains on track and ends next December. On the back of fiscal discipline and certain structural reforms (e.g. tax administration), public finances are becoming healthier over time, and the small fiscal deficit of 0.5% of GDP seen last year is forecast at this level in the MLT while public debt remains firmly on the decline. Public debt is expected to fall from the level of 68.9% of GDP at the end of 2016 to about 50% this year, and it could be below 40% by 2024. Moreover, its external share, though still dominant (58% of the total), is following a similar downward trend, which will contribute towards reducing the vulnerability to change in foreign investor risk sentiment.

While structural reforms are gradually moving forward, more is required to contain the large burden of public wages (a quarter of current spending), and particularly to reform the many SOEs that highlight the state’s large economic weight and uncompleted economic transition process; the SOE reform and better management goals are only slowly proceeding due to vested interests. Meanwhile, the stable banking sector has strengthened, as reflected by a sharp decline in the NPL ratio, from 17% in 2016 to 4.7% last September, although state banks continue to show relative weaknesses and reliance on external funding has increased (please note the negative net foreign asset position of 5.1% of GDP in November 2019 compared to -2.4% in 2016).

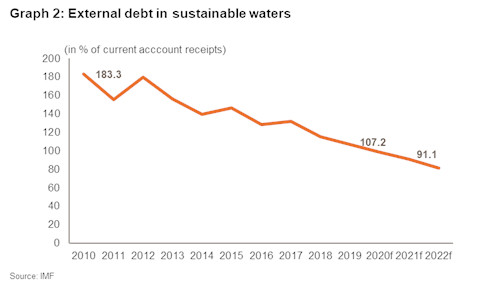

More sustainable external debt on a downward trend

Serbia’s financial risk has improved significantly compared to 2016. External debt ratios, on a downward trend since peaking in 2015, fell further from 73.9% to 65.5% of GDP and from 128% to 107% of current account receipts between 2016 and 2019. This favourable trajectory is expected to continue at a decent pace in the MLT, bringing the external debt to more sustainable levels (below 50% of GDP by 2023).

Serbia’s positive economic and financial momentum allowed the country to successfully issue Eurobonds last year and replace some of its costly USD-denominated debts, and the robust external liquidity position has remained fairly stable since 2016. Foreign exchange reserves have been on an upward trend, swollen by strong FDI and the Central Bank’s purchases to limit the dinar’s appreciation pressures last year. Consequently, foreign exchange reserves maintained their import cover, fluctuating at around 4.5 months (thus offsetting the stronger FDI boost on imports), while remaining sufficient to cover three times the ST debt and twice the debt service. The latter reached 21.7% of current account receipts last year but remains very far from the higher levels seen prior to 2015. It is expected to be around 20% in 2020-2021 before gradually decreasing to about 13% in the long term, alongside the forecast decline in external debt.

EU accession, albeit remote, is the top political driver

President Vučić, whose Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) runs a solid majority coalition in Parliament, has been facing growing opposition and various risks of political instability. Since the last quarter of 2018, street protests have been taking place as part of the opposition’s attempts to blame the President’s alleged authoritarianism, rising media controls, corruption and the encouragement of violence to stem the opposition, but despite this, given Mr Vučić’s popularity and a fragmented opposition, he is almost sure to win the elections scheduled for next spring. However, if the opposition were to boycott the elections, this could harm the SNS and Mr Vučić’s legitimacy, notably vis-à-vis the EU. Using the EU as leverage is not an innocent manoeuvre, as Serbia’s top government target and policy driver for the coming years lie in the continued reform process towards EU accession. EU negotiations began in 2014 and membership is expected, in the most optimistic scenario, by 2025 at the earliest. However, lukewarm EU enthusiasm about a new wave of enlargement, especially without a preliminary EU reform, will most likely delay Serbia’s EU accession.

The other major obstacle to joining the EU is the persisting absence of recognition of Kosovo’s sovereignty. A compromise will be necessary to overcome this deadlock, potentially via land concessions on both sides. Since last year, the EU and the USA have been pushing for a risky and unpopular territory swap between Kosovo and Serbia, and since the failure of this attempt, bilateral relations have again deteriorated and the conflict risk has increased. In order to put pressure on Serbia to recognise its independence, last year Pristina imposed a 100% tax on imports from Serbia and decided to set up its own army. Even though the future is uncertain, with a new opposition government in Kosovo and renewed EU and US diplomatic attempts to find a solution, ups and downs are likely to characterise their bilateral relations until the necessary diplomatic deal is reached.

Looking ahead, the road to the EU will also be rocky because President Vučić, while taking a pro-European stance, also wants to maintain good relations with Russia to please the majority of the Serbian population. That being said, at this stage and in spite of frequent nationalist rhetoric in the country, the EU remains Serbia’s most likely prospect. Outside Kosovo, further political violence risks (rated by Credendo at 3/7) come from unresolved border issues with other Balkan countries, particularly Croatia. Moreover, the actions of Serb minorities in Bosnia-Herzegovina continue to represent instability risks due to the fuelling of nationalist sentiment in Serbia and in the Balkans as a whole, where tensions have worryingly been increasing in recent years.

Analyst: Raphaël Cecchi – r.cecchi@credendo.com