Laos: Eroding liquidity and unsustainable debt service outlook could lead to debt relief agreement with China

Event

Laos is facing renewed fuel shortages since August while inflation is at huge levels. These economic troubles highlight the eroding liquidity and costly fuel imports driven by high commodity prices and a sharply weakened local currency. This context of acute financial difficulties brings fears of sovereign default given the challenging debt repayments ahead. However, China’s expected support to make the debt service outlook more sustainable mitigates those threats.

Impact

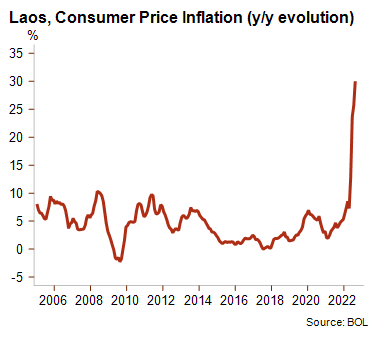

The Laotian economy is suffering from the detrimental impact of high commodity prices on several economic indicators. The widening current account deficit (expected at 6.5% of GDP this year) is expected to deteriorate further in 2023 due to heightened commodity and capital goods imports related to infrastructure projects. As a result, the country’s liquidity is under pressure as chronically low foreign exchange reserves barely allowed an import cover of 1.5 months last March. By then, this level is expected to fall further on the back of depleting foreign exchange reserves and soaring imports. Those developments explain the continued downward trend of the kip, the local currency, which has lost 65% of its value over the past 12 months (on 10 September 2022). Hence, inflation accelerated to 30% in August, i.e. the second highest rate in Asia.

Lower liquidity puts Laos in a challenging situation given the upcoming high external debt payments. From 2023 onwards, the debt service on external debt – about half of which is owed by the public sector – is expected to largely exceed foreign exchange reserves. The Covid-19 pandemic had a severe impact on Laos’ financial risk, as public debt, which is largely external, climbed by more than 50%, from 62% to 95% of GDP between 2019 and 2021. Previously, the external and public debt had already ballooned due to hydropower projects and China’s high-speed railway project linking Laos to China (completed in the end of 2021). Therefore, the current tightening of the global financing conditions, interest payments above 20% of revenues and the possible public debt increase above the 100%-of-GDP threshold in 2022 (as a result of the kip depreciation) bring concern about a potential sovereign default.

However, the fact that Laos’ debt service payments are mostly due to China (owning about half of Laos’ external public debt) makes the prospect of sovereign default very unlikely in the short term. Indeed, Laos’ key, close and reliable financial, economic and political partner would not tolerate a destabilising debt default from its South-Eastern Asian neighbour. Although Laos was eligible to the Debt Service Suspension Initiative in 2020 and 2021, the country did not apply to join it, possibly in order to avoid the transparency requirements related to the IMF financing and to preserve its (expensive) access to the Thai capital market. In a context of tighter global financing conditions, market access to refinance commercial bonds has become nearly undoable in practice. Therefore, the only way to avoid default lies in a debt relief agreement with China, and the debt restructuring option would not harm giant China. Recent history also shows that Laos might revert to asset transfers, as in 2020 when a Chinese state-owned enterprise took majority control of Laos’ power grid. At the same time, the country’s single ruling communist party is committed to its plan to cut public expenditures and raise revenues to bring the fiscal deficit under 5% of GDP as from next year.

The outlook for the ST political risk (6/7) is negative given liquidity erosion. The same severe negative outlook applies to the business environment risk (F/G) due to huge inflation, a record low kip and moderate real GDP growth forecasts (+3.8% in 2022 and +4% in 2023 according to the probably too optimistic World Bank forecasts of last July). Indeed, the weakening external demand, the sharp Chinese slowdown and high fuel prices are expected to hit exports and domestic demand over the next six months, thereby affecting GDP growth. As for the MLT political risk (6/7), the negative outlook will depend on the external debt evolution and the extent of a probable debt relief agreement, and other potential measures, with China.

Analyst: Raphaël Cecchi – r.cecchi@credendo.com