Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia: What are the risks that could affect the economic growth of the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia in 2021?

Introduction

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy is significant. Annual global GDP fell by 3.3% in 2020 compared to 2019 (WEO April 2021) while world trade fell by 5% on average in 2020. At European Union level, real GDP dropped by 6.2% (6.6% for the eurozone, according to Eurostat). The Czech Republic has been one of the countries in Central Europe whose GDP has fallen the most. Real GDP in 2020 was 5.6% lower than in 2019, while that of Slovakia fell by 5.2% and that of Poland by just 2.7%. These open countries are closely linked to the German economy, which posted real GDP growth of -4.9% in 2020. A large part of their goods exports consists in vehicles and parts, as well as electrical and mechanical machinery.

What is the expected performance in 2021?

Despite the still virulent impact of Covid-19, the evolution of European production and demand should return to positive territory in 2021, driving real GDP growth (see graph above). While there are several reasons for this, the first and most important one is that the figures for 2020 fell so much that they reached a very low base, meaning that the following year can only be better. Secondly, consumer spending – along with the authorities’ support measures – should drive an economic rebound in Europe. Indeed, progress in the European vaccination programme should allow a large part of the population to be immunised in the second half of 2021, gradually making it possible to regain the pre-crisis lifestyle. This should allow private consumption to pick up from a very low level and some households will be able to spend all the cash they have saved during the pandemic (see graph below), given the reduced uncertainty. Thirdly, economic activity has managed to adapt as best it can to the decline in contact and social interaction. Fourthly, the fiscal support announced by several countries and the European Commission for 2021 (mainly the Next Generation EU funds and the huge fiscal package announced by the Biden administration) should propel investments and consumer demand. However, although economic activity is increasing compared to the previous year, this does not mean that it will return to its 2019 level. In Europe (UK included), it will be necessary to wait until 2022 at best for economic activity to return to its pre-crisis level in real terms, with discrepancies across countries. Moreover, the outlook is still subject to great uncertainty related to the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic.

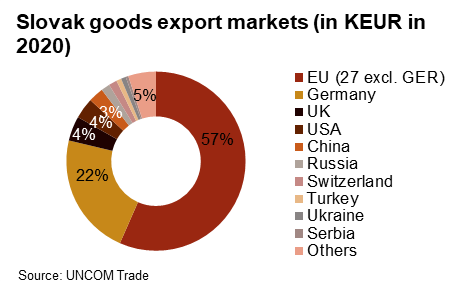

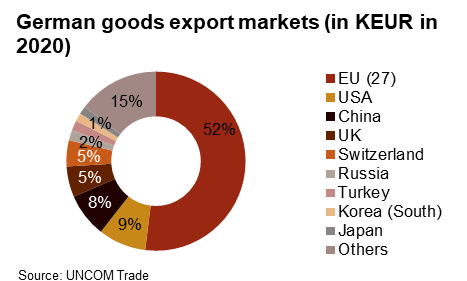

Another key element in understanding the performance of these economies is the interaction between the different countries (and sectors) and especially their dependence on Germany. The graphs below show that exports of goods from Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia depend heavily on Germany. This is especially the case for the Czech Republic, whose economic growth is strongly correlated with exports, but is less so for Polish and Slovak exports even though Germany remains an important trade partner. Consequently, the demand from Germany will strongly influence domestic production (e.g. automotive production) in these three countries, while the extra-European demand for German goods will benefit them indirectly. Besides, the European Union (including Germany) is their privileged economic partner given it represents around 70-80% of their goods exports. The expected rebound in real GDP for Germany (3.5% in 2021, 3.1% in 2022) and the Eurozone (4.2% and 3.6%) bodes well for economic activity in the three countries discussed even if uncertainty remains great. This reliance on the EU for the open economies is a strength in times of economic boom; nevertheless, it is a weakness in times of (global) recession, which we could see in 2020.

What are the main risks to the outlook?

As explained above, the two main risks arise from the concentration of their export markets (Europe, Germany) as well as the concentration of their export sector (automobiles, electrical and mechanical machinery, etc.). This reliance on the automotive sector could pose a risk in the short, medium and long term, given the challenges facing the sector (Brexit, CO2 emissions targets, the end of combustion-engine vehicles, the rise in electric vehicle sales, the high investments needed, the disruption in the semiconductor supply chain, etc.). The disruption of semiconductors is a major source of concern for the automotive industry (OEM included). Although it started at the end of 2020, the impact was only really felt in the first quarter of 2021 and is expected to be just as significant in the second. Production was stopped on all continents, sometimes for a few days and sometimes a for few weeks. This drop in production is expected to slow the recovery of the automotive sector further.

Another element that could put the short-term outlook at risk is the evolution of vaccination campaigns in Europe. While the latter has fallen behind, thus delaying the return to normal, the appearance of certain variants could prolong the duration of the pandemic, reduce the efficacy of the vaccines and hence deepen its impact on economic activity. As a result, the economic recovery might be weaker than currently projected, more jobs could be lost and more companies might default. It should be highlighted that so far, a large wave of default has been avoided thanks to the significant support measures provided by the authorities (estimated by the IMF at 27.8% of GDP in Germany, 5.4% in Poland, 4.4% in Slovakia and 15.4% in the Czech Republic in April 2021).

Other factors need to be looked at closely to get a good idea of the risks of these countries. First, Brexit: although it has already taken place, its impacts are still in their early stages – that is to say, the supply chain is not yet established with all the administrative measures and other procedures to allow smooth trade between the blocs. The UK is an important economic partner of Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Hence, a drop in trade is likely in the first half of the year, given the time necessary for businesses to adjust to new constraints. To illustrate, UK imports from the European Union in February 2021 decreased by 34% year on year, according to Eurostat (although part of this decrease is assumed to be due to the Covid-19 crisis).

Tensions between the USA and the EU and to a lesser extent the USA and China should also be seen as potential risks to the outlook. Indeed, although EU/US tensions have eased since the new tenant of the White House arrived, some thorny issues remain. While the digital economy tax reform project led by the OECD is no longer blocked by the US administration, a new tax (‘digital levy’) is being studied by the European Commission, which could revive tensions between the two blocs. In addition, we see that the USA and China are among the top 10 export markets for Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

In addition, high commodity prices as well as the tightening financial conditions, combined with the gradual withdrawal of government aid, could pose problems for less creditworthy companies as higher commodity prices could increase their input costs. On the other side, tighter financial conditions would not only increase the cost of funding but also reduce access to credit, which is often badly needed for entities hit hard by the Covid-19 crisis. It is worth noting that SMEs are particularly vulnerable to a tightening of the financial conditions given not only their reliance on the banking sector but also their usually thin equity cushions, low liquidity buffers and non-diversified revenues. Finally, a premature withdrawal of policy support could not only lead to a sharp tightening of financial conditions but also disrupt a nascent economic recovery.

In the longer term, significant risks include the increase in the cost of labour in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland (to a lesser extent) compared to their regional counterparts. Although this is positive for domestic consumption, it erodes their competitiveness.

Analyst: Matthieu Depreter – m.depreter@credendo.com