Angola: High oil prices are driving recovery, yet vulnerabilities are rife

Event

After a brutal multi-year recession shrinking the economy by 10% since 2016, Angola’s economy has strongly rebounded since 2021 and GDP growth is expected to reach 2.9% and 3.4% in 2022 and 2023 respectively. High oil prices and recovering oil production have contributed to a rapid decline in the public-debt-to-GDP ratio, which was exacerbated by this year’s sharp appreciation of the kwanza, thus significantly improving the country’s public finance figures. Nevertheless, Angola’s growth performance and projected debt sustainability are still highly reliant on an unpredictable oil market.

Impact

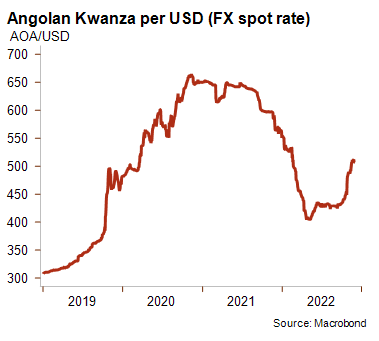

Since 2021, Angola’s oil output finally started rising again after years of falling hydrocarbon production while international oil prices surged after the Russian invasion in Ukraine. This has given a very strong boost to Angola’s economic performance and financial position. Together with higher oil revenues, the implementation of the National Development Plan (2018-2022) under the coordination of an IMF financial support programme (December 2018-2021) instigated the gradual economic recovery. The government committed to the implementation of some critical reforms such as VAT implementation, a floating exchange rate and the partial privatisation of national oil company Sonangol. Following a period of heavy depreciation of the local currency resulting from the release of the kwanza in 2018, the high oil prices since 2021 helped turn the trend around (see graph below). Moreover, a successful ten-year USD 1.75 billion Eurobond sale in April 2022, shows improved investor confidence in the country.

Angola’s kwanza increased sharply against the USD in the early 2022 pre-election period but has been adjusting downward again since September, resulting in a 10% year-on-year appreciation against the USD in November 2022. The public-debt-stock-to-GDP ratio is expected to drop from its peak of 136% of GDP in 2020, to approximately 56% in 2022 and could even fall below 50% as of 2024, according to the IMF’s latest expectations. The sharp tumble in Angola’s public external debt ratios is driven by the jump in GDP and strong performance of the kwanza, while the nominal external debt stock level in US dollar terms has remained relatively stable since 2018. Moreover, domestic debt maturity has been lengthened and the government has been cautious in taking on new loans as some debt management reforms were introduced. At the same time, yearly debt servicing costs have been reduced substantially since 2020, thanks to a debt reprofiling deal with China. Angola has been by far China’s largest African debtor in recent years. In 2021, Angola secured a debt rescheduling deal with China in the form of three years of payment relief, deferring almost USD 6 billion in repayments and opening up another USD 700 million tranche of IMF financing under its programme. As of 2023, the moratorium ends and debt will need to be repaid again. However, Angola has already been accelerating its debt repayments to China, making use of high oil revenues.

When President João Lourenço took office end 2017, the country embarked on a very long and complicated transition after decades of autocratic rule which had centralised all political and economic power in the hands of José Eduardo dos Santos and his entourage. With the new president coming from the same MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) party as his predecessor, Angola’s transition can hardly be called a fully democratic one. In fact, in August 2022, presidential and legislative elections were marred by irregularities and the results were contested by the MPLA’s old civil war rival and main opposition party Unita, that claimed it had won. The MPLA’s reaction was one of repression and intimidation by security forces, claiming victory and extending their 47-year rule. Although power has shifted hands, the MPLA’s rule is still considered to be authoritarian, leading to a sustained risk of social unrest and political destabilisation. Still, international support for President Lourenço’s transition and anti-corruption campaign has helped Angola secure an IMF bail-out in 2018. Nevertheless, the population is confronted with MPLA-dominated public institutions and lacking economic opportunity beyond the wealthy oil sector. In fact, the government’s main diversification policy (PRODESI) has had little results up until now and Lourenço's anti-corruption efforts have paralysed many institutions. These institutions are stuck between the fear of maintaining ‘old practices’ and a lack of skills needed to execute new policies, which often leads to an authoritarian way of policy-making by decree.

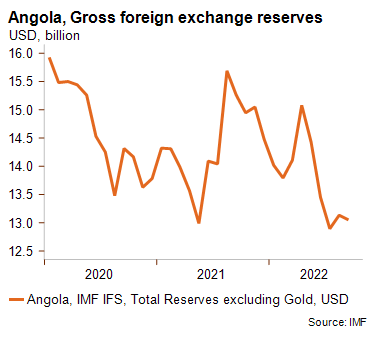

Angola has been struggling with persistent high levels of inflation for decades. Over the past three years, tighter monetary policy was implemented to reduce inflation. However, a real drop is only expected as of next year, as high global prices have kept this year’s inflation expectation at 15%, despite monetary efforts. Angola’s external and fiscal balances are extremely exposed to oil price volatility. Oil makes up for almost 96% of all foreign exchange earnings and around 60% of government revenues. This continues to be the most important risk to Angola’s outlook, knowing that most indicators usually follow the ups and downs of the oil sector. The Angolan government did not manage to be sufficiently forward-looking during the recent boom period as foreign exchange reserves levels were not strengthened to bolster liquidity for when oil revenues start falling again (see graph below). However, the pressure on reserves is also due to the country’s high import dependency (deficient agricultural and manufacturing sector) in an environment of soaring global prices.

Another major near- to longer term risk for Angola relates to the global path towards decarbonisation and to falling oil production. Knowing that Angola is one of the most oil-dependent economies in the world, diversification efforts need to be sharply accelerated in order to cope with the gradual decline of global fossil fuel consumption. Like most countries in the region, Angola is also subject to substantial risks related to climate change. Therefore, Credendo’s MLT political risk classification for Angola remains stable in category 6/7 for now.

Analyst: Louise Van Cauwenbergh – l.vancauwenbergh@credendo.com